The Space Shuttle, or as it was officially named, Space Transportation System (STS), was one of the most emblematic chapters in NASA’S history and also the most catastrophic. In this series of 5 articles, we will go through the concept, execution, flaws, and tragedies that haunted the program.

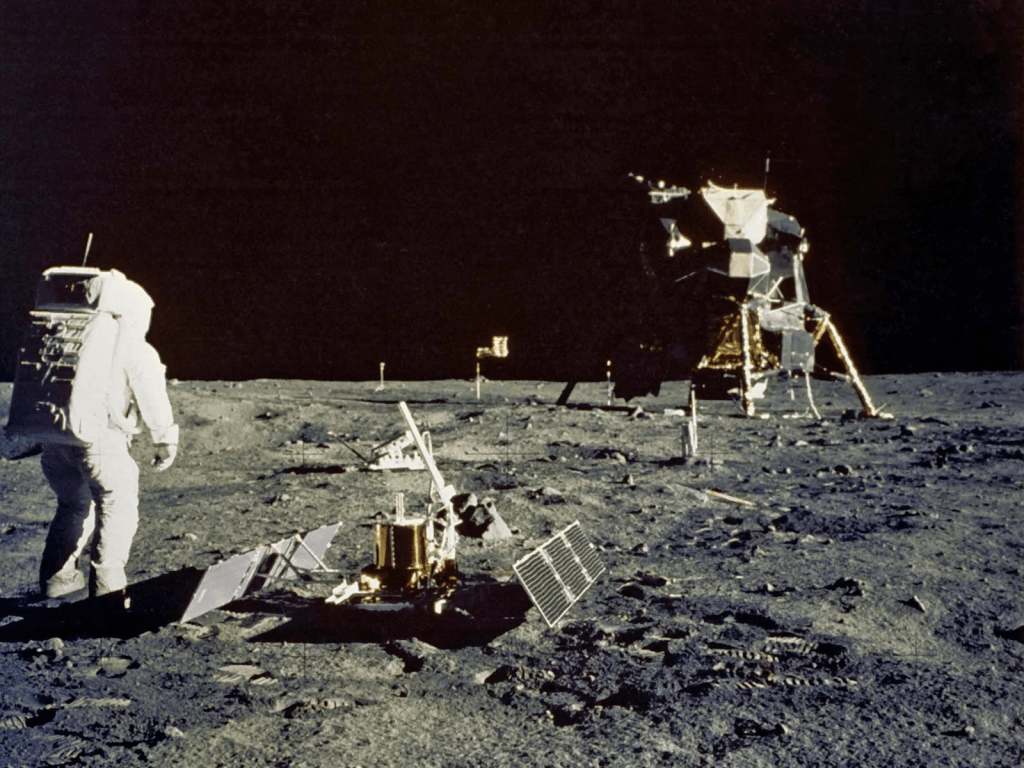

July 21, 1969, at 02:56 UTC, the world watched in awe when the Apollo 11 commander, Neil Armstrong, left the lunar module Eagle and became the first man to set foot on the Moon. The successful mission was, in fact, one giant leap for mankind, as Armstrong later said, but for NASA and the American government, it represented something else. For years, the Americans had been mercilessly beaten by the Soviets in the so-called space race but that day, the crew of the Apollo 11 redeemed their pride, proving that hard work and the good ol’ American ingenuity can be unstoppable. Well, hard work, ingenuity, and a whole lot of money too, NASA funding peaked, by the late 1960s, at a staggering 4,5% of the federal budget.

When the crew of the last Apollo Moon mission came back home, in 1971, the public interest in space exploration had already wined down and Congress decided to drastically cut the flowing of money to NASA.

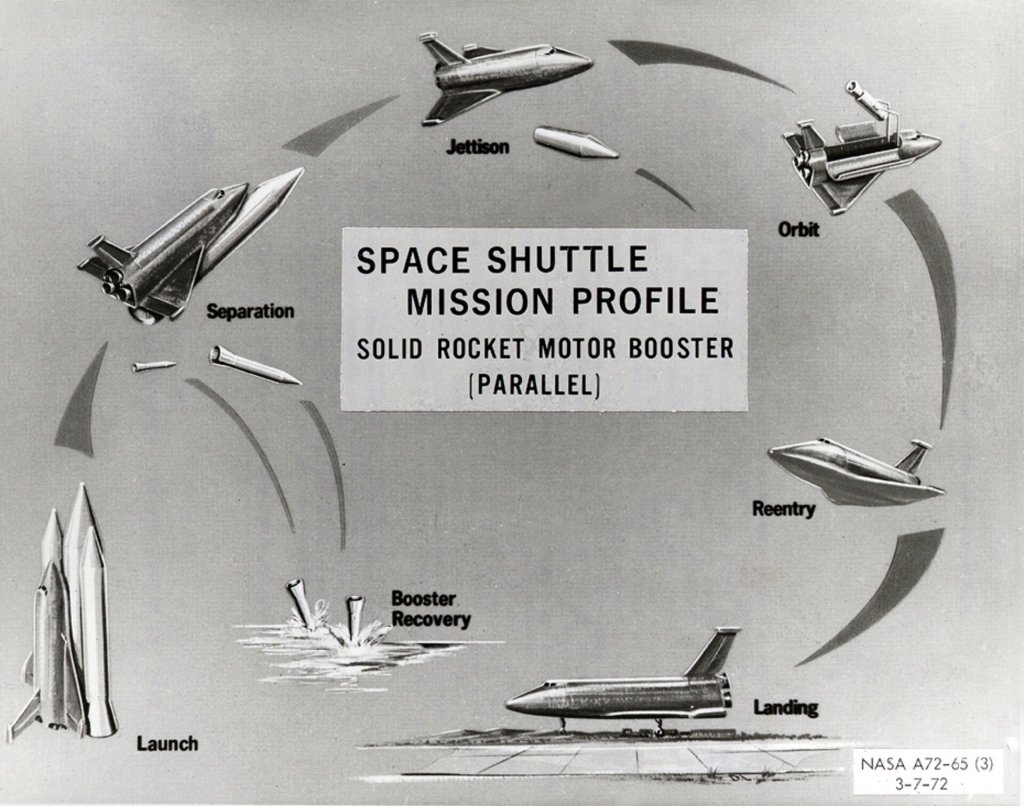

The minds in charge of NASA knew that the days of meager funding would inevitably come and as early as 1969, they started the development of a cost-effective program called Space Transport System or STS. The idea couldn’t be simpler, instead of one-time-use rockets, this program consists of a series of spaceships that could be reused time and time again. It would take off like a rocket, and land like an aircraft.

Ernest Von Braun, the father of the Apollo program (and also a former Nazi engineer), didn’t like the idea, he thought NASA should keep pushing the rocket technology and send a manned mission to Mars as soon as possible. But the concept of the STS gained hearts and minds among the government and in 1972, the Nixon administration gave NASA the green light to go ahead with the program.

The Space Shuttle idea also had a very important ally, the military. The guys in uniform saw it as the perfect vehicle to transport spy satellites and, who knows, maybe a couple of nukes into space too. “What the heck, let’s scare the bejesus out of those atheist commies!!!“

The Space Shuttle was never meant for deep space travel. As the name implies, the ship was designed to transport astronauts and equipment from Earth to a space station in orbit around the Earth and from this station, a different ship would travel to the Moon and beyond.

NASA received almost 30 different designs of the space shuttle from all the American air and space companies and after careful examination, they decided to go with the one from Rockwell International.

In 1974 the prototype was ready for some initial atmospheric flight tests. At this point, the shuttle was still without engines and had to piggyback a heavily modified Boeing 747 to take off and reach operational altitude. This first orbiter was christened Enterprise.

The picture above shows the moment when the space shuttle Enterprise is detached and starts a test glide. The 747 used as a carrier was a second-hand purchase from American Airlines and it was still wearing the company’s livery at the time.

The details of the machine

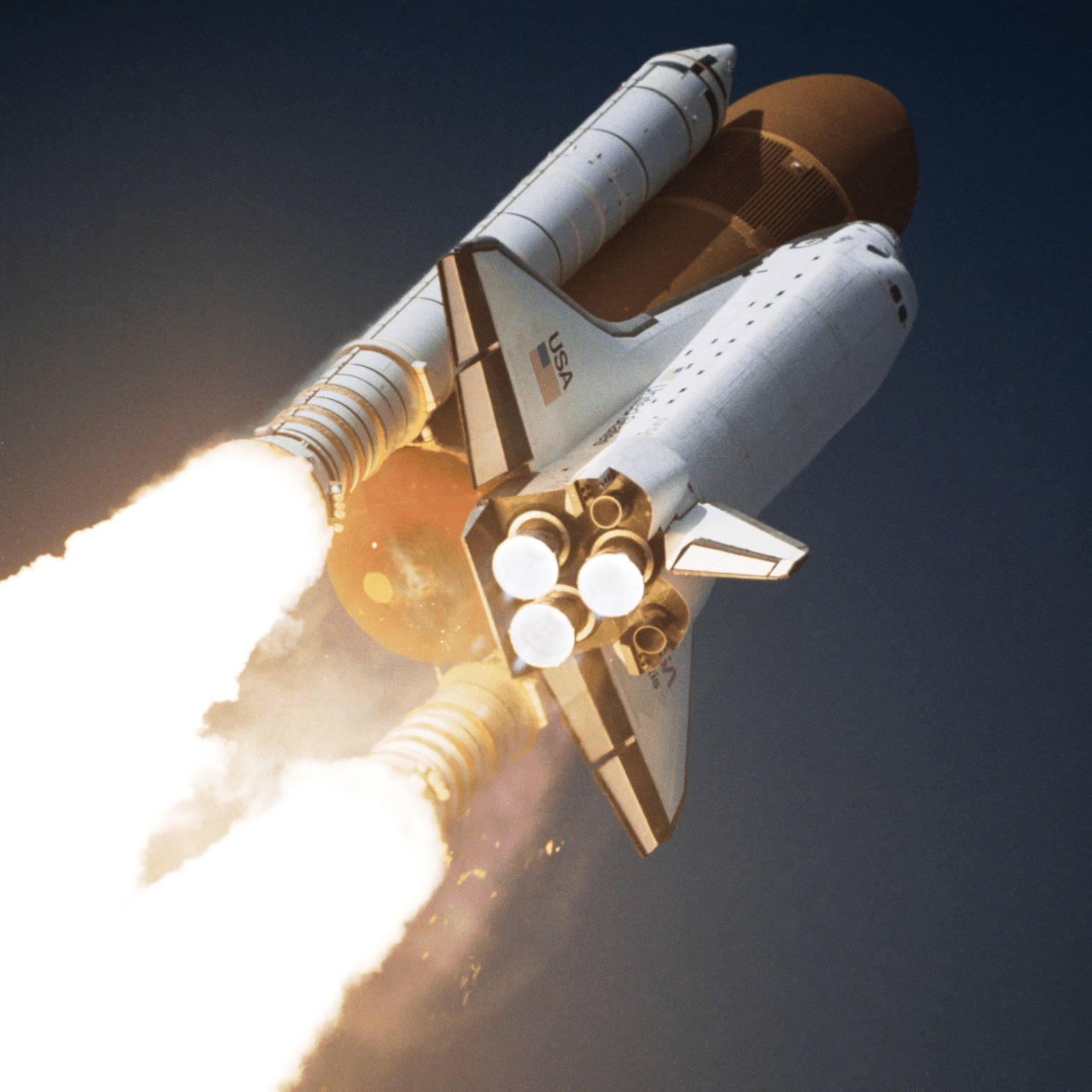

Simplicity and efficiency ruled the whole project. The shuttle or orbiter was designed to be powered by 3 main engines but to escape the Earth’s gravitational force, it needs the help of two solid rocket boosters. The ship is attached to the humongous fuel tank, in between the rockets. At a certain altitude, the boosters are released and after the ship consumed all the fuel, the tank is also jettisoned, leaving the shuttle free for a gracious space flight. The rocket boosters were also to be recovered and reused after each flight.

The journey back from space is not an easy task. The reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere is extremely dangerous since, at this point, the shuttle will be traveling at an incredible Mach 23, or 17,500 miles per hour or 7 km per second. The pilot must start the reentry at a 40° angle of attack and slowly bring the craft parallel to the ground and fly it like an airplane as soon as it starts to gain aerodynamic controls. Talking about working under pressure.

The friction of the air against the ship is so intense that without a thermal shield, the whole spacecraft would simply melt away. The bottom portion, most of the nose section, and the edges of the wings are covered with special ceramic tiles, measuring 6×6 inches and the thickness is between 1 and 5 inches. The tiles provide efficient thermal isolation to temperatures up to 1,260° Celsius, but they are extremely fragile against impact. (picture above).

A flawed spacecraft

Is hard to say if NASA was just being overly optimistic about this new program or if they were trying to guarantee the funding for it, but one thing is for sure, they certainly promised way more than they could deliver. NASA said the shuttle would make orbital space travel accessible to the masses and it would be so cost-effective that the agency could afford to send a shuttle to space twice a week.

To enhance the concept of a reusable spacecraft, the orbiter was conceived to be powered by three main engines, which considerably reduced its cargo capacity. To make the matter even worse, the cost of rebuilding those engines after each flight proved to be more expensive than the engines that equipped the rockets of the Apollo program. Some scholars argue that the shuttle could be more useful if it was originally designed as a glider, powered by detachable engines.

The first mission of the program was the STS-1, the orbiter Columbia took off on April 12, 1981, and came back 54,5 hours later, having orbited the Earth 37 times. Columbia carried a crew of two, mission commander John W. Young and pilot Robert L. Crippen. (picture above).

The launch happened on the 20th anniversary of the first human space flight, performed by the Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin. This was a coincidence rather than a celebration; a technical problem had prevented Columbia to take off 2 days earlier. That was the first of a series of flight delays and cancelations that marked the program during its existence. All sorts of technical gismos plagued the orbiters throughout the years, from falling heat shield tiles to frozen software.

During the first half of the 1980s, the shuttles performed many different missions; launching and repairing satellites, taking astronauts to and from the space station, and so on. Those missions were more or less successful but the constant flight delays were a source of frustration among the team. NASA was still trying to show the world they were able to keep a regular flight schedule, even if it was a much lower pace than the unrealistic 2 flights per week originally promised.

The technical problems faced by the team were perfectly understandable; they were dealing with a new and complex machine that needed time to adjust and improve. It was the rush to keep a steady schedule of flights that proved to be a catastrophic mistake.

In the next chapters, we are going to revisit a couple incidents that almost ended in tragedy and also the two horrible disasters that claimed the lives of 14 astronauts.