If you follow this blog, you probably have noticed that I love motorsports. I can spend hours watching all kinds of races on TV, but I am not a big fan of NASCAR. First, I don’t like watching races on oval tracks in general, but what disgusts me the most is how they encourage drivers to play dirty on the track, which inevitably leads to fistfights or any other deplorable behaviour by the drivers.

However, I do admire the cars themselves. The big American cars powered by the old-school pushrod V8 are fantastic. The new generation of machines is even better; the design has moved away from the awkwardness of the big sedans and has become closer to a genuine sports car.

NASCAR is the most popular form of motorsport in the USA. The list of things I despise about it is the very things that make thousands of fans go to the races every weekend. People want to see more than racing; they want to be entertained. From its beginning, deeply rooted in unlawful bootlegging in the 1920s and 1930s, to the unfair driving methods of the modern drivers, the good ol’ boys of NASCAR always provided good and controversial entertainment.

But the colourful behaviour of NASCAR is not limited to what I listed here; there was a time when cheating became rampant, and teams played a game of cat and mouse with race officials.

“YOU DONT RACE CARS; YOU RACE THE RULE BOOK.” – Smokey Yunick.

During the 1960s, NASCAR builders devised clever ways to cheat the rule book; the idea was simple: make the car lighter and faster, even if it meant bending the rules. Everything was considered fair game, as long as you weren’t caught.

Some tricks indeed resemble the kind of stuff that would come out of Wili E. Coyote’s mind. These are some of the wild examples: using lightweight wood to build the roll cage and then painting it to look like steel, helmets and radios made out of solid lead, and casually left them in the car when they went onto the scales, filling the cars’ frame rails with shotgun pellets that could be dumped during the race through a secret hatch, and even frozen springs that would lower the vehicle below the legal height as they warmed up.

The master illusionist

In the eyes of the fans, these “talented” builders were heroes. More than bending the rules to get faster cars, they were using creativity “to fight the establishment,” keeping the outlaw spirit of NASCAR alive.

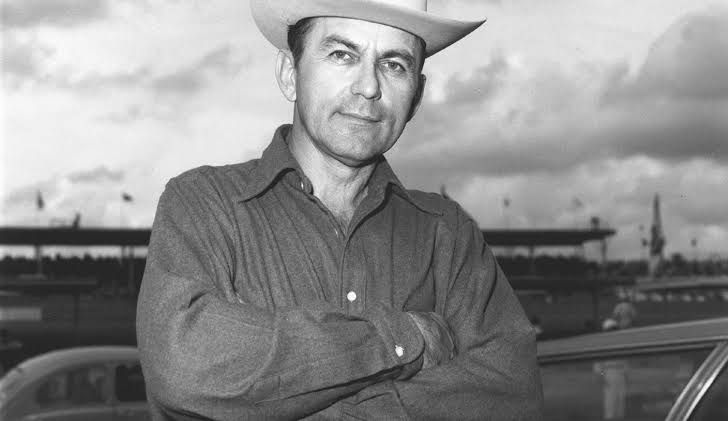

Among those builders, there is one name that reached the status of legend. One guy whose creativity in creating his own rules made him larger than life; Smokey Yunick.

Henry “Smokey” Yunick was born on May 25, 1923. He was the son of Ukrainian immigrants who owned a farm in Neshaminy Falls, Pennsylvania. At the age of 16, he dropped out of school to run the farm full-time. It was during this period that Yunick demonstrated his mechanical talent by improvising solutions for broken farm equipment and even building a tractor out of a junk pickup truck.

During his spare time, he built and raced motorcycles, earning his nickname due to the smoke produced by his bikes.

Yunick’s military service during WWII is a mystery; it is a point where legend and reality collide. According to a New York Times article, Yunick enlisted in the US Air Corps in 1941 and served as a bomber pilot with the 97th Bombardment Group, based at Amendola Airfield, Italy. He flew a B-17 named “Smokey and his Firemen” and survived nothing less than 50 missions over occupied Nazi Europe before being transferred to the Pacific theatre. This outstanding military resume would be enough to elevate the guy as legendary; the only problem is, according to official military records, Yunick was drafted from civilian life as a welder in January 1943, at the age of 19, in Philadelphia at the enlisted rank of Private. He served on active duty from February 1944 to March 1946, when he left the Air Corps as a 2nd Lieutenant.

The Best Dam Garage in Town.

In 1947, Yunick opened a repair shop named Smockey’s Best Damn Garage in Town at 957 N. Beach St, in Daytona Beach, Florida. His reputation as a good mechanic spread quickly around town, and Marshall Teague, a local stock car team owner, invited him to be part of the team.

In 1951, Yunick faced his baptism of fire when he prepared a Hudson Hornet for Herb Thomas (picture above) to compete in the second edition of the Southern 500 in Darlington, South Carolina. Thomas, who is considered to be the first NASCAR superstar, won the race, propelling himself and The Best Damn Garage in Town to popularity.

F-Indy

Smokey made NASCAR his home, but his ingenuity also found its way to Formula Indy. In 1959, he created a car with a reversed engine rotation that, theoretically, would improve the weight distribution when turning left on race tracks.

The idea is quite simple: most automotive engines rotate counterclockwise as viewed from the flywheel, and the torque vector points to the right side of the car (if it is a longitudinally mounted engine, of course). If we could make the motor rotate in the opposite direction, the torque would “pull” the car’s weight to the left, improving load distribution for the left-hand only turns of American oval tracks.”

Smokey called his creation The Reverse Torque Special, which was a Kurtis-Kraft 500H powered by an Offenhauser 4-cylinder engine, spinning in the opposite direction.

Veteran Duane Carter had no trouble qualifying the car 12th and finished 7th in the 1959 edition of the Indy 500. Even if the car had a respectable performance during the race, it wasn’t enough to prove that the engine rotation is, in fact, critical to influencing the car’s behavior on race tracks.

Smokey’s creative mind never rested. In 1964, he created a genuinely innovative Indy machine, the Capsule Car. Once again, Yunick was trying to relocate some of the car’s loads (in this case, the driver) to the left.

The team failed to qualify for the 1964 Indy 500, and Yunick abandoned the idea of improving the car. It now resides in the Indianapolis Motor Speedway’s Hall of Fame Museum, where it is often on display.

In the 1950s, Yunick was heavily involved with Hudson, the only American automaker that initially took NASCAR seriously. Due to the rising popularity of stock car racing in the South, by the early 1960s, all the other automakers began to join the trend.

In the 1960s, controversial hot rodders like Smokey Yunick and Carroll Shelby earned the respect of the Big Three automakers—Ford, GM, and Chrysler—through their innovative “shade tree engineering.” The CEOs had to acknowledge that these experts knew how to squeeze power and speed from their vehicles better than anyone else. To succeed in racing, the automakers realized they needed to collaborate with them.

They never said I couldn’t. -Smoke Yunick-

There are quite a few stories about Yunick’s cheating techniques. The NASCAR officials used to joke about it, saying that the rule book has a dedication to Smokey on its first page.

Smokey worked for various automakers during his years in NASCAR. He raced Chevrolets in 1955 and 1956, Fords in 1957 and 1958, and Pontiacs from 1959 through 1963.

After leaving Pontiac, Yunick renewed his partnership with Chevrolet. At this point, GM didn’t want to have a works NASCAR team, and The Best Damn Garage in Town became the “unofficially official” Chevy team. Does that sound sketchy? You bet. But those years became, perhaps, the most colorful period in his career. Some of his achievements are memorable, but they gravitate between reality and fantasy.

Smokey’s most famous story happened during the 1968 Daytona 500. He brought his highly modified Chevy Chevelle for the technical inspection, and race officials went over every inch of the car looking for violations. They even took out the fuel tank to inspect it!

Smokey received a list of nine violations that needed to be corrected before the car could be raced. “You’d better make it ten,” Smokey said before jumping into the car and driving off, leaving his fuel tank still lying on the ground!

The trick here is simple: regulations specify a maximum capacity for the fuel tank, but they don’t say anything about the fuel lines. Smokey built an 11-foot (3-meter) coil of 2-inch (5-centimeter) diameter tubing for the fuel line and voilà; he just added about 5 US gallons (18. liters) to the car’s fuel capacity. Years later, Yunick declared that this episode had never happened; it was just a story that became folklore, although some people swear they had seen it happen.

Honey, I shrunk the Chevelle.

One famous episode in Smokey Yunick’s career is steeped in fantasy and can be recounted in various ways, depending on the storyteller. Some claim that Smokey built a scaled-down version of a Chevelle, measuring either 7/8 or 15/16 of the actual car’s size. While race officials noticed something unusual about it, they couldn’t pinpoint the exact issue. The car successfully passed technical inspection and, benefiting from reduced aerodynamic drag, dominated the NASCAR season in 1967. Although this makes for an entertaining story to share with friends at parties, it is simply not true.

But what Yunick did on this particular Chevelle is nothing short of amazing.

This was a 1966 Chevelle (although Smokey called it 1967) that was part of 3 cars developed in partnership with Chevrolet. Yunick improved the aerodynamics with intelligent solutions, like narrowing the bumpers, lowering the roof, raising the floor, repositioning the bumpers close to the fenders, flattening and smoothing the floorpans to act as bellypans, and covering every opening to minimize air drag.

Yunick’s tricks worked wonderfully, and during tests, the #13 Chevelle was way faster than the competition. Even if the car retained the factory’s original dimensions, as the picture above shows, the extensive modifications led to its disqualification.

Trans Am Camaro.

When Chevy released the Camaro in 1967, Yunick was in charge of developing it for the “Pony Car War,” which was fought in the Trans Am class. Not only was the livery of the famous #13 Chevelle adopted, but more importantly, all the aerodynamic enhancements as well. Smokey took the Camaro to the salt flats in Bonneville and broke several class records over there.

Not a cheater, but a developer.

Of course, not everyone saw Smokey as a hero. “Smokey was the worst or best, I’m not sure what you’d call it,” said Ray Fox, who drove stock cars in the 1950s and was later a car owner and a NASCAR official. “He was always trying to get away with something. I think Smokey had the idea [that] if you could have four things wrong and get one through, that was good.

Gradually, NASCAR relaxed its rules, and Yunick’s ideas, especially in the field of aerodynamics, became the norm, helping to make NASCAR what it is today.

Yunick also contributed immensely to the development of high-performance versions of the venerable Chevy small-block V8. All those tricks were extensively used not only by General Motors but also by the high-performance parts industry.

A mechanical genius

Smokey applied his mechanical creativity not just in competition, but also in everyday situations.

He wrote a column, “Say, Smokey,” for Popular Science Magazine in the 1960s and 1970s. In it, he responded to letters from readers regarding mechanical conditions affecting their cars and technical questions about performance. He also wrote for Circle Track magazine.

Smokey held several U.S. patents, including variable ratio power steering, the extended tip spark plug, and reverse flow cooling systems. In 1961, he also developed air jacks for stock cars, but NASCAR wouldn’t allow their use.

The revolutionary Fiero

Smokey spent years developing the “Hot Vapor Engine,” in which the fuel is heated up to 400 degrees Fahrenheit (204 degrees Celsius) before entering the engine. Theoretically, the gasoline would reach the combustion chamber completely vaporized, allowing it to fill it up more efficiently.

In 1987, Yunick modified a stock, 4-cylinder Pontiac Fiero, achieving impressive results. The sturdy yet outdated 151-cubic-inch (2.5-liter) Iron Duke 4-cylinder engine now delivers over 50 miles per gallon, produces 250 horsepower, and generates 230 ft-lbs of torque. It runs more smoothly than any 4-cylinder engine you’ve ever experienced and can accelerate from 0 to 60 mph in as little as 6 seconds!

Could this car, presented to the world nearly 40 years ago, be the answer to all our questions? Perhaps, but the auto industry ignored it, and this new technology was forgotten.

At the end.

Yunick left NASCAR in 1970 with a sense of mission accomplished. At the time, he hadn’t realized how much his work would influence the next generation of builders.

Smokey closed the Best Damn Garage in Town in 1987, claiming that there were no more good mechanics.

He could be spotted at the NASCAR pits during the 1990s, even though he was no longer managing any team. During this time, he was battling bone cancer and other illnesses.

In 2000, he told a reporter:

“I was diagnosed with everything but pregnancy. Finally, about a month ago, I took all the medicine and threw it in the trash can. I told the doctor, ‘I’m done with this shit. If I’m going to die, I’m going to die. Don’t even talk to me about it anymore.’ I picked up horsepower, about 70 percent. I feel 100 percent better. I came away from wheelchairs, those things you push, canes. Now I’m walking by myself, all that in 20 days.”

“I just went up and down. I didn’t know what was happening. I was so weak I couldn’t do nothing. I really didn’t want to live because I couldn’t do nothing. I’m starting to get back in the ball game. I may be going to drop dead because I won’t take the medicine, but I ain’t taking no more. If I’m going to die, let’s get it over with. I’m headed for 78 now, and I’ve had enough of everything, with no regrets. I had a good life.”

Smokey lived on his own terms without caring much about rules or authority, and that was how he chose to live during his final days. He died on May 9, 2001, at the age of 77.

He became a member of more than 30 Halls of Fame, including the International Motorsports Hall of Fame and the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America, was a two-time NASCAR Mechanic of the Year, and many of his engines, tools, and personal items are on display in museums, including the Smithsonian.

The character Smokey in the third movie of the Pixar franchise Cars, voiced by Chris Cooper, is based on him.

“Smokey was so ingenious. He was definitely the most ingenious mechanical head that we ever had. He was so far beyond. If he’d been working for NASA on the moon program, we’d have been up there in 1950.” — Humpy Wheeler, president of Charlotte Motor Speedway.

I have only scratched the surface of Yunick’s life with what I’ve shared here. To give you an idea, his autobiography, *Best Damn Garage in Town: The World According to Smokey*, was published in July 2001 and is available as a three-volume collection. The audiobook version, titled *Sex, Lies, and SuperSpeedways, Volume 1*, was narrated by his longtime friend, John DeLorean.

Feeling generous? Visit my “Buy Me a Coffee” page

Great biographical story, Rubens. I thoroughly enjoyed learning about the life and accomplishments of Smokey Yunick. I was particularly impressed by the 4-cylinder Pontiac Fiero creation that got 50 miles per gallon and could accelerate from 0 to 60 mph in 6 seconds! What are we messing around with electric cars (fire starters) for then? My four-year-old grandson loves Pixar’s Smokey!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That Fiero also impressed me. It blows my mind that automakers ignored all that technology. Thanks for stopping by, Nancy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fire starters… LOL. I love it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Light weight wood rollcage? well if you’re gonna die…..

Great story Rubens. All motor sports have a genius lurking in it’s history. Not a fan of NASCA either, I had never heard of the gentleman so thanks for the info.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am glad you enjoyed the article.

I knew pieces and bits about Yunick’s career; I even believed the scale-down Chevelle was a true story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantástico 💯

LikeLiked by 1 person