Top picture credit – Jeremy- Google Photos.

If you have been following the news lately, you know that Canada is facing an unprecedented threat against its own existence. The country that once was our strongest ally is swiftly becoming the aggressor.

In this new scenario, Canadian patriotism is on the rise. I plan to embrace this trend by publishing a few articles about the machinery that contributed to building Canada’s reputation as a strong and free country—a beacon of democracy and tolerance in the world, always ready to stand against fascism. In this first article, I will tell the story of the most heroic ship in the records of the Canadian Navy, the HMCS Haida

A Monument Ship

One thing that excited me when we moved from Manitoba to Ontario in 2019 was the abundance of military museums throughout the province. The first place I chose to visit isn’t a museum in the traditional sense; it’s a monument dedicated to the Tribal-class destroyer HMCS Haida, located in Hamilton, ON.

In the course of two wars, Haida destroyed more enemy equipment than any other Canadian vessel, earning it the nickname “The fightingest ship in the Royal Canadian Navy.”

Our Fighting Lady

-“Come, cheer up, my lads, ’tis to glory we steer,

To add something more to this wonderful year,

To honour we call you, as freemen not slaves,

For who are so free as the sons of the waves?“-

The first verse of “Heart of Oak”, the official march of the Royal Navy, and adopted by the navies of the Commonwealth.

By the mid-1930s, it was clear that another war against Germany was looming on the horizon. In response, the British began preparations by developing the Tribal class, also known as the Afridi class. This class of destroyers was designed in 1938 to provide modern weaponry for the Commonwealth Navies in anticipation of the impending fight against German U-boats.

The Tribals evolved into fast, powerful destroyers that emphasized guns over torpedoes in response to new designs by Japan, Italy, and Germany. They were well admired by their crews and the public while in service, known for their strength, and often regarded as symbols of prestige.

HMCS (Her Majesty’s Canadian Ship) Haida was built by Vikers-Armstrong Shipyard, in Newcastle – England, on September 29, 1941. The ship was commissioned on August 30, 1943. She was named to honor the seafaring Haida Nation, the Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America.

Haida began its service during World War II, escorting supply convoys to Murmansk, Russia. These convoys traveled throughout the winter, always above the Arctic Circle, taking advantage of the constant darkness. This made it more difficult for the Luftwaffe to spot them and direct submarine wolf packs to attack.

One can only imagine the hardships of the crew during those exhausting escorting missions. The unbearable frigid temperatures, the terror of the constant darkness, and always on the lookout for enemy submarines.

On Christmas Day, 1943, a German task force of a few destroyers and the Battle cruiser Scharnhorst was sent to intercept the convoy RA55A, which left the Kola inlet in northern Russia for Britain. The heavy weather made it impossible for the German destroyers to keep up with the pace of the battle cruiser, and at 9:21 a.m., Boxing Day, the Scharnhorst was spotted by the Brits. The German captain knew his ship was heavily outnumbered, but instead of retreating, he attacked the convoy at full speed.

The British cruisers ‘Sheffield‘, ‘Belfast‘ and ‘Norfolk‘ immediately engaged the single German ship. Shortly after, the battleship ‘Duke of York’ and the cruiser ‘Jamaica‘ joined the battle. After 3 hours of exchange fire, the Scharnhorst was sent to the bottom of the ocean. While the HMCS Haida didn’t participate directly in this battle, the ship helped to shepherd the convoy, keeping it safe and in formation.

HMCS Haida and the ship’s men earned their first battle honor, an honorary distinction recognizing active participation in the battle for this Arctic service, during which the German battlecruiser Scharnhorst was sunk.

Operations along the French coast

On 10 January 1944, she was reassigned to the 10th Destroyer Flotilla at Plymouth and took part in Operation Tunnel and Operation Hostile, patrolling the Bay of Biscay and along the French coast of the English Channel.

The first victory

“ There are no roses on a sailor’s grave,

No lilies on an ocean wave,

The only tribute is the seagulls’ sweeps

And the tears his sweetheart weeps “

An old German Navy song.

During the night of 25 April 1944, Haida, with Black Prince and the destroyers Ashanti, Athabaskan, and Huron engaged the German 4th Torpedo Boat Flotilla comprising the ships T29, T24, and T27.

Haida‘s crew skillfully sank the T29 and heavily damaged the T24. The limping German boat managed to scape ro St. Malo, in the company of T27.

On the night of 28 April, T24 and T27 attempted to move from St. Malo to Brest. They encountered the destroyers Athabaskan and Haida off St. Brieux, which were performing a covering sweep as part of Operation Hostile. The Athabaskan was torpedoed and sunk in the engagement, and T24 is credited with sinking it.

Haida ran T27 aground and set the vessel on fire with shelling. Of the Athabaskan’s crew, 128 were lost, 44 survivors were recovered by the Haida, and 83 survivors became prisoners of war of the Germans in France.

Operation Overlord

During the weeks leading up the invasion of Normandy, Haida and its sister ship Huron continued to operate as part of the 10th Destroyer Flotilla, patrolling the western entrance of the English Channel.

Perhaps the ship’s most important mission was to be part of the attacking force of the Operation Overlord. On 8–9 June, Haida was part of Task Force 26, which engaged the German 8th Destroyer Flotilla, comprising Z32, Z24, ZH1, and T24 northwest of the Île de Bas.

Haida and Huron, once again working as a deadly team, sunk the Z32 in the Battle of Ushant. Following the fall of Cherbourg to the Allies, the German E-boats were transferred to Le Havre, freeing up the 10th Flotilla (The “E” in “E-boat” is derived from the German word “Eilboot,” which translates to “fast boat” or “speedboat.”). The flotilla was then given the dual role of covering Allied motor torpedo boat flotillas and search and sink missions against German shipping along the French coast.

On 24 June, while on patrol in the English Channel off Land’s End, Haida and the Britsh destroyer Eskimo were called to engage in a U-boat hunt, started by a squadron of B-24 Liberators. After the American bombers dropped their depth charges on the target, the two ships began their onslaught. After several attacks, the submarine surfaced and attempted to run. Haida and Eskimo fired all their guns, and in a matter of minutes, the U-971 started to sink. Not a lot of German sailors had the chance to escape. Haida rescued only six survivors.

The never-ending fight.

On July 14, 1944, Haida and the Polish ship ORP Błyskawica intercepted a group of German ships in the Île de Groix area near Lorient. The battle saw two submarine chasers, UJ 1420 and UJ 1421 destroyed, one German merchant ship sunk, and two others set afire.

Besides the fancy name of “submarine chaser,” the UJ 1420 and UJ 1421 were basically captured French trawlers, converted by the German Navy as submarine chasers. They were equipped with sonars, microphones, depth charges, and some light armaments

In November 2002, Pierre-Adrien Fourny from Boulogne-France brought to light some interesting details about the ship that became the UJ 420, the Eylau.

“My grandfather, Eugène Fourny, managed the family fishing company owning the trawler Eylau, which was taken by the Germans and converted to a warship. It was sunk by Haida and other destroyer near Groix Island in South Britanny. I will always be very proud of the Eylau; the little French trawler needed two Allied destroyers to be sunk. I am also very happy because, after the war, the French government gave a new motor trawler to my grandfather. “

On August 5–6, Haida participated in Operation Kinetic, a mission focused on patrolling waters near the French coast. The force attacked a German convoy north of Île de Yeu, resulting in the sinking of the minesweepers M 263 and M 486, the patrol boat V 414, and the coastal launch Otto. During the battle, a shell exploded in one of Haida’s turrets, causing a fire that killed two crew members and injured eight others, ultimately rendering the turret inoperable. The Allies then attempted to engage a second convoy; however, they were repelled by shore batteries and had to withdraw without inflicting significant damage on the German merchant vessels.

The last missions of the war.

Thanks to its versatility, destroyers could be employed in various missions. The HMCS Haida and its crew were kept pretty busy during the last Allied push against nazi Germany. In September 1944, the ship sailed to Halifax, Nova Scotia, for well-deserved repairs and a new radar. The ship was sent back into action in Scapa Flow in January 1945.

Haida’s crew saw their fair share of combat during those last months of war, either escorting convoys or hunting U-boats.

The ship participated in one of the last Royal Canadian Navy engagements of the Second World War when she escorted convoy RA66 from Vaenga from 29 April to 2 May.

Long gone were the days when the U-boats were the predators. At this point of the war, they were more likely to be the prey, but even though a “wolf pack” led by an experienced captain could still inflict some damage. The convoy RA66 was attacked in transit, and Haida and Huron were targeted by torpedoes fired by U-boats, which narrowly missed. In the skirmish, two German U-boats and the British frigate Goodall were sunk. The convoy safely escaped in a snowstorm.

On May 07, 1945, Germany surrendered, ending the conflict in Europe. Haida was then assigned to relief operations at Trondheimsfjord, Norway. From 29 to 31 May, Haida and Huron, as part of the 5th Escort Group, were sent to Trondheim to take over custody of surrendered U-boats.

The war in Europe had ended, but American forces were still engaged in combat against Japan in the Pacific. The destroyers Haida, Huron, and Iroquois arrived in Halifax on June 10, 1945, to receive the necessary tropicalization refit to prepare them for deployment to the Pacific. However, the Japanese Empire surrendered later that summer before the refit was completed.

Captain, my Captain.

(photo by Lt Herbert J. Nott, Canada. Dept. of National Defense, courtesy Library and Archives Canada / PA-141695)

Commander Henry G. DeWolf was the captain of HMCS Haida between 1943 and 1944, during the thick of the war. He became one of Canada’s most decorated naval heroes. DeWolf served more than 40 years in the Royal Canadian Navy and was eventually promoted to vice-admiral.

Ironically, DeWolf suffered from seasickness throughout his naval career and said he could only sleep while sitting up.

The Cold War

The cannons of World War II had barely cooled when, on March 5, 1946, at Westminster College in Fulton, USA, Winston Churchill warned the world about the next threat to democracy:

-“From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent.” – His speech officially marks the beginning of the Cold War.

Haida was in inactive reserve for approximately one year but in 1947 the ship underwent a refit for updated armament and sensors.

This was Haida’s revised firepower:

- 3 × 4.7-inch (119 mm)/45 Mk.XII twin guns

- 1 × 4-inch (102 mm)/45 Mk.16 twin guns

- 1 × quadruple mount 40 mm 2 pounder gun.

- 6 × 20mm Oerlikon twin cannons

- 1 quad launcher with Mk.IX torpedoes (4 × 21-inch (533 mm).

- 1 rail + 2 Mk.IV throwers (Mk.VII depth charges

The ship received modern radars, sonars, and a state-of-the-art electronic gun-fire control unit.

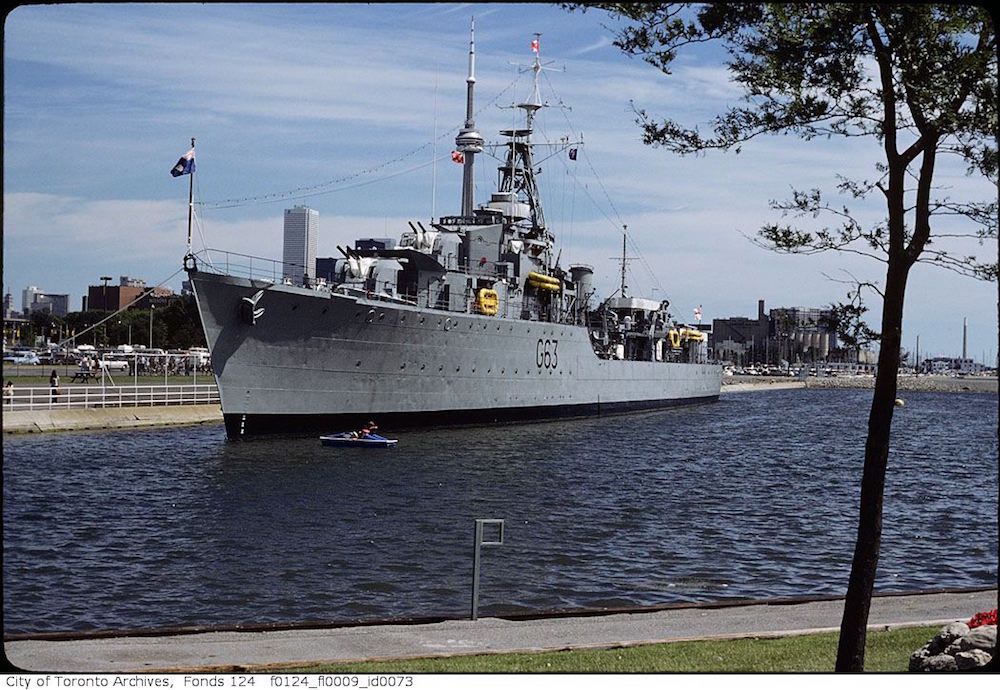

She returned to the fleet, still carrying the pennant number G63, in May 1947.

When the Korean War started on 25 June 1950, Haida was once again activated for war duty. The ship received another refit in July 1950, with various new armaments, sensors, and communications systems. She was recommissioned on 15 March 1952 and carried the pennant DDE 215. She departed from Halifax on 27 September for Sasebo, Japan, arriving there on 6 November after passing through the Panama Canal.

(photo by Allan F. Jones, Canada. Dept. of National Defence, courtesy Library and Archives Canada / PA-138197)

Haida relieved Nootka on November 18, 1952, off the west coast of Korea. Her first mission was to perform aircraft carrier screening and coastal patrol missions. The real combat started on 4 December 1952 when the ship took part with the destroyer escort USS Moore in shelling of a railway yard in Songjin, a coastal battery, and North Korean troops.

Targeting trains and rail yards would become a thing for the Allied war ships in Korea. On 18–19 December, Haida failed to join the exclusive “Trainbusters Club” when an enemy train she attacked managed to hide in a nearby tunnel. Haida returned to patrol on 3 January 1953, escorting aircraft carriers and bombarding the coast. On 29 January, Haida finally made in the “Trainbusters Club”, destroying a train north of Riwon. The ship eliminated a second train on 26 May, and detonated a drifting anti-ship mine on her return to Paengyang-do. At this point, the Korean war was heading to an agreement between the parts involved, and with the de escalation of the combat, Haida was sent home on June 12, 1953.

On July 27, 1953, an armistice was signed, ending organized combat operations and leaving the Korean Peninsula divided much as it had been since the end of World War II at the 38th parallel.

Unfortunately, China and North Korea did not respect the ceasefire, leading to Haida’s second tour in Korea on December 14, 1953. An Allied naval presence was reestablished around South Korea, making this tour relatively easy. Haida returned home to Halifax on November 1, 1954.

Following its operations in Korea, Haida took on Cold War anti-submarine warfare duties alongside other NATO units in the North Atlantic and the West Indies. Back in Canada, in May 1956, Haida, accompanied by Iroquois and Huron, made port visits to various cities and towns along the St. Lawrence River.

The end of her career

It was during one of her deployments in the Pacific that Haida faced her last battle; not against enemy guns but against the power of nature. In an interview given to CBC in 2023, Andy Barber, a Haida’s veteran, tells the story of how the ship survived the fight against a powerful typhoon.

Barber may not have served during wartime but he was on the Haida’s bridge when it was almost lost to Typhoon Grace, off Japan in 1954.

He remembers the 2,500-tonne destroyer being tossed around on the ocean like a toy, and recalls the superhuman efforts of his shipmates to keep her afloat.

– “We were running into these waves that were, like, 60 feet high, crashing over the top of the ship,” – At one point, the Haida was caught in a confluence of waves, swamping the bow while the stern with its spinning propellers was raised out of the water.

– “We all went flying to one side and that whole ship just about somersaulted,” Barber said. “It was only through the grace of God … that it straightened out.” –

After 15 years of many battles and missions, Haida‘s aging hull and infrastructure were becoming problematic. She went through a refit in January 1958 for hull repairs, to protect her electronic equipment. She was brought to the docks again in 1959 for further refits. Haida set sail for the West Indies in January 1960; however, equipment malfunctions, including a failure of her steering gear on April 3, forced her to return to Halifax. A hull survey in May discovered extensive corrosion and cracking, prompting her to go into drydock for the rest of the year. In June and July 1961, she underwent additional repairs after more cracking was found during operations in heavy seas that March. More cracks were detected in March 1962, resulting in another refit that lasted through February 1963.

Haida resembled an old warrior with too many wounds who could no longer fulfill her duties. The time for her retirement has come.

Saving a hero.

In 1963, prior to being paid off, HMCS Haida sailed on a farewell tour of the Great Lakes. This inspired a group of businessmen to form Haida Inc. The purpose of this enterprise was to acquire the ship, save it from the scrap yard, and preserve her as a memorial to the men and women of the Royal Canadian Navy.

Haida was open to the public for many years at Ontario Place in Toronto (picture above). She was acquired by the Province of Ontario in 1970.

In 1990, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada designated HMCS Haida as a National Historic Site.

The responsibility for maintaining the ship was transferred to Parks Canada in 2003. Extensive repairs to the hull were completed (picture above), and she arrived at its new home at Pier 9 in Hamilton Harbor on August 30, 2003, coinciding with the 60th anniversary of its commission.

HMCS Haida is the last survivor of the twenty-seven Tribal Class destroyers built for the WWII. Thirteen of which were lost during the conflict. The ship is one of only three remaining of the over four hundred Canadian warships from the Second World War, a time when Canada’s navy was the third largest in the world!

This monument serves as more than just a tribute to the sailors who courageously served in the Royal Canadian Navy during both peace and wartime. It represents a time when nations united to combat tyranny—a time when soldiers, sailors, and airmen from various countries regarded each other as brothers and sisters, standing together in the fight for freedom. Governments may come and go, but these memories shall never fade away.

Great article, coincidentally I had a ham radio contact this week with one of the site managers from HMS Belfast in London. He’s ex-Italian Navy

LikeLiked by 2 people

Waht a coincidence indeed.

HAM radio is fascinating, you should write an article le about it.

LikeLiked by 1 person