Italian Campaign – (July 9, 1943–May 2, 1945)

Following the Allies’ victory over the Axis forces in North Africa, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill persuaded the Americans to capitalize on the momentum and open another front, this time in the Mediterranean region. Churchill’s idea was simple: he wanted to open a second path towards Berlin, going through Italy. He assumed that invading and defeating Italy wouldn’t be difficult; he even referred to the country as ‘the soft underbelly of Europe’.

The campaign would also force the Germans to stretch their troops and supplies beyond the limits, fighting on 3 different fronts: France, Russia, and Italy.

The Italian campaign proved to be much more complicated than Churchill had previously thought. Starting in 1943, other countries joined the fight, providing much-needed help to the Allies. Among those nations, there was a South American country that, until then, considered itself ‘neutral’, Brazil.

Getulio Vargas

At the outbreak of the war, Brazil faced a tough decision: President Getúlio Vargas, a Nazi sympathizer, was from Rio Grande do Sul, a southern state with a massive number of German and Italian immigrants. During his rule, he established strong economic links with Germany. Additionally, Vargas was a dictator who took power in 1937, further complicating the situation.

But Vargas wasn’t a fool. Uncertain if Germany would come out victorious at the end of the war, he declared Brazil a neutral state.

However, keeping Brazil neutral during wartime was easier said than done. The Royal Navy established a blockade that heavily restricted the German maritime trade, particularly after 1941. Depriving Brazil of an important customer of our raw materials.

But there was no lack of customers for our products. Soon, Brazilian ships became a common sight across the Atlantic, transporting badly needed goods, back and forth to England. Naturally, those vesels became a target to the Nazi U-Boat fleet. March 2, 1941, marks the first attack against a Brazilian ship, but it was only after a couple of ships were lost that Vargas was forced to declare war against Germany on January 15, 1942.

The picture above shows the “Araraquara”, which was sunk on August 15, 1942, by the U-boat U 507. A total of 131 lives were lost that day.

Declaring war was one thing, but actively engaging against the Axis forces was something entirely different. The Allies wanted a genuine commitment from Vargas, one that could only be achieved if the Brazilian armed forces were equipped with modern weapons.

When World War II started, Theodore Roosevelt assured Americans that the U.S. would stay out of the conflict. However, recognizing the desperate need for aid among the nations fighting against Germany, his government introduced the ‘Land and Lease’ Act. Passed by Congress in March 1941, this law empowered the president to send war supplies, food, and equipment to any country considered “vital to the defense of the United States” during the war. It provided aid mainly to Britain, the Soviet Union, and China—without immediate payment—amounting to about $50 billion. This legislation also paved the way for the U.S. to supply weapons to Brazil.

Soon after Brazil and the USA shook hands on this deal, the Americans flooded our bases with new toys. Things like guns, jeeps, trucks, tanks, and airplanes.

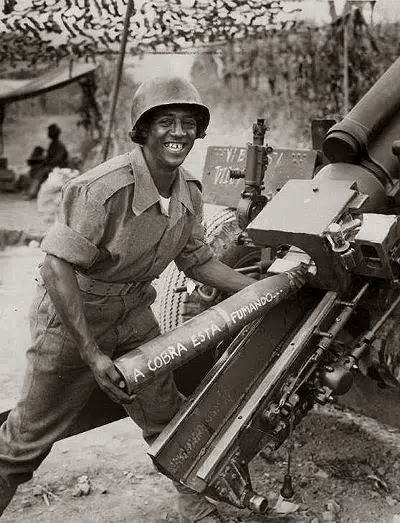

The Smoking Snake

Just like any other dictator before and after him, anywhere in the world, Getulio Vargas was a shameless liar. He promised to send troops to Europe as soon as they were equipped with the new weaponry, but it didn’t happen. Although by 1943, the construction of an Allied base in Brazilian soil was already in full swing. The picture above shows Vargas (the guy in the white suit in the back seat) having a laugh with Theodore Roosevelt, during a visit to the Parnamirin Air Base construction site.

By 1944, the time for the Brazilian president to fulfill his promises had finally come. The Italian campaign proved much harder than Churchill had predicted; the fierce German resistance and the harsh environment imposed an unimaginable strain on the Allied troops. The Allies needed reinforcements as soon as possible.

Vargas delayed the decision to send the troops as much as possible, and at some point, the population and the media were also convinced it would never happen. One reporter from a big Brazilian newspaper once said, “I think I’m going to see a snake smoking a pipe before I see a Brazilian soldier at war”.

As a humorous answer to the reporter, an Army soldier drew a picture of a smoking sneake. The picture became famous among the military, and what was initially just a joke evolved into something serious. The original drawing was a bit crude, and the Walt Disney Studios created a more refined version (pictured above). Without hesitation, the Brazilian Army adopted the symbol as the official insignia of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force.

On July 16, 1944, the first wave of 5075 “Smoking Snakes” arrived in Naples, Italy. The deployment was completed over the following months, involving a total of 25,000 personnel. Way less than the 100,000 Vargas had originally promised.

The Brazilian Expeditionary Force was part of a massive coalition of allied nations in an effort to open a corridor through the Italian mainland all the way to Berlin. The Nazis knew very well the importance of keeping that door shut at any cost, and both sides fought fiercely. As a result, the Italian campaign was one of the bloodiest of the war.

A considerable number of Brazilian soldiers were of Italian descent, which made the effort to liberate the country from fascism even more meaningful. They helped liberate cities like Massarosa (pictured above), Monte Plano, and Monte Castelo.

The Brazilian Expeditionary Force had a brief participation in the Italian Campaign, from September 1944 to May 1945, but they often faced the thick of the action.

The inexperienced Brazilian soldiers fought head-on against ferocious German forces determined to hold their position in battles such as the one to liberate the city of Montese. (pictured above).

“No matter how many lands I travel

God, don’t let me die

Without returning home

Without carrying my chevron

This V that symbolizes

The victory to come.“

-Excerpt of the Expeditionary’s song.-

“Only the dead have seen the end of war.” George Santayana.

At the conclusion of the war, approximately 1200 Brazilian personnel from the army, navy, air force, and merchant navy lost their lives in combat. Their courage will be forever remembered not only by Brazilians but also by Italians.

In the next chapter, I will tell the fascinating story of Parnamirin, a massive air base the Americans built in Brazil, and its vital role in the Allied victory.

Your account of Brazil’s involvement in WWII and their significant contribution to Allied victories was quite informative and interesting. A conspiracy theory that is still circulating claims that Hitler and some of his top ranking honchos escaped to South America after the war. That would explain all the Volkswagens in South America. Haha! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am not sure if Hitler had time to escape, to South America but a lot of German military personnel did. During my early years of my professional journey, I worked with Mr. Otto, a retired mechanical engineer who had served with the Afrika Corps during the war, and this is just a tiny example of this “exodus.” If I try to explain the German influence in Brazil and Argentina, I might as well write a book.

In Southern Brazil, it is rare to find someone without German or Italian blood in their veins. In my case, I have a mix of both.

LikeLike

Brilliant article, sadly we have new and unexpected challenges to face now

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much.

You are right. Now, there’s another fascist power rising up, and this time, it will be way more difficult to defeat it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

😦

LikeLike