The amazing story of a rogue RAF pilot and his vendetta against the Gestapo.

WWII was the bloodiest conflict in human history, it is impossible to be precise about how many lives were lost as a consequence of the hostilities but the number lies somewhere between 50 and 85 million. It was a time when Presidents, Prime Ministers, and dictators asked their citizens to abandon their civilian lives to become soldiers and go to the battlefields across the globe, to fight, kill and die for their countries. The war revealed an immense number of heroes and unfortunately, a great number of cowards too.

From five-star Generals to the privates, all of them were forced to make decisions that were meant to take or save lives. Decisions that brought victory or defeat one step closer. There are thousands of stories about bravery and self-sacrifice and a good number of them were driven by revenge.

This is the story of Baron Jean de Selys Longchamps, a man determined to bring swift vengeance against one of the most feared terror organizations that ever existed, the Gestapo.

The invasion Belgium

On the 10th of May 1940, the German armed forces unleashed Operation Fall Gelb (Case Yellow), invading at the same time Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Belgium. At this point, there were Nazi flags already flying in Poland, Denmark, and Norway. The Germans seemed unstoppable.

The French and the British concentrated their armies in Belgium, in hopes of stopping the Germans there. During the first two days of battle, the Nazis managed to cross the dense Ardennes forest, encircling the Allies and pushing the offensive towards the English Channel.

The Germans reached the Channel after five days, gradually reducing the pocket of the Allied resistance, and forcing them back to the sea.

The tactics of the Blitzkrieg had prevailed once again. The Wehrmacht overwhelmed the enemy with superior manpower, better equipment, and over-the-top motivated troops. For the Germans, it was payback time.

On May 26th, the Brits initiated Operation Dynamo, in which they managed to evacuate more than 338,000 Allied soldiers from the beaches of Dunkirk. The retreat marks the end of the British military operations on Continental European soil for the time being and also the end of the French Army as an effective fighting force.

With no other option on the table, the Belgians surrendered on May 26, avoiding the certain slaughter of its entire army.

The road to Paris was wide open.

The relentless Baron.

Among those soldiers rescued in Dunkirk, there was a young Belgian Army Captain who would become more than a footnote in the history of WWII. Baron Jean de Selys Longchamps, DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross), was born into the Belgian nobility, on May 31st, 1912. He inherited his title from his father, Baron Raymond Charles de Selys Longchamps. The young Longchamps had dropped out of the Catholic University of Leuven to start a tranquil career as a bank clerk in Brussels.

His fate after the outbreak of the war was no different from thousands of other young men around the world. Longchamps was drafted into the Belgian Army and became a cavalry officer with the 1er Regiment des Guides.

After the fall of Belgium, he was rescued at Dunkirk and went to England. Once there, he joined the Allied soldiers who were crossing the channel, going back to defend France.

France fell fairly quickly, a victim of faulty intelligence and the reluctance of the army’s high command to adapt the tactics to this new, fast-paced warfare imposed by the Germans. On the 14th of June, 1940, the citizens of Paris watched in disbelief, Nazi troops marching through the city. Baron Longchamps fled to Marrocos, avoiding being captured by the Germans.

Upon arrival, he was arrested by the Vichy French authority and sent to Marseille. The Baron was becoming quite an expert in escaping from the enemy and once again he was able to elude his captors and fled to Spain. From there he found his way back to safety in Great Britain.

The Royal Air Force was desperate for recruits and Longchamps was offered a chance to become a pilot. He didn’t think twice and immediately applied to join the RAF academy. The only problem was, at 28 years old, he was considered too old for the job, but the Baron would let such a small hiccup like this block his plans, and he lied, straight face, about his age on the application.

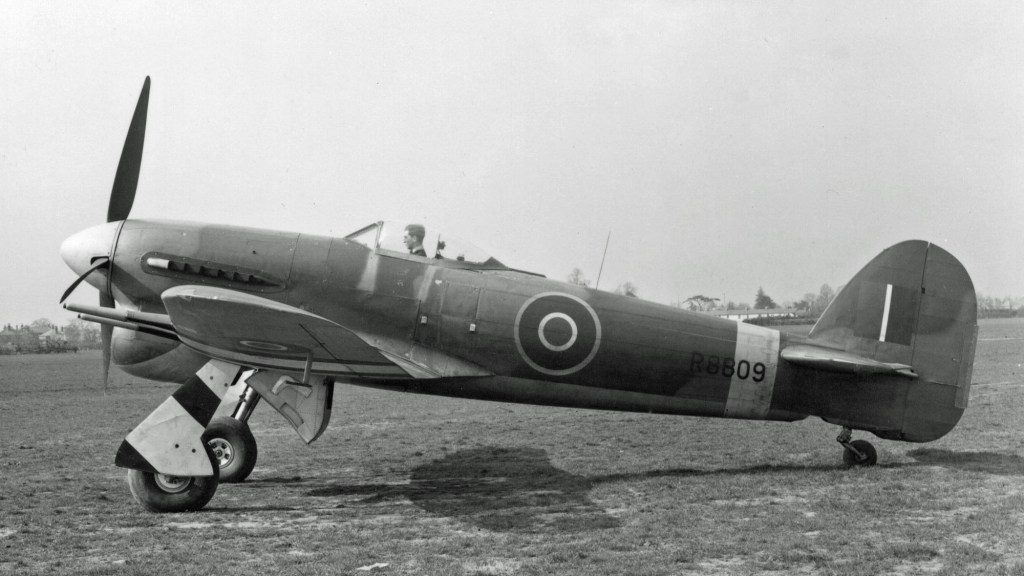

After completing the flight training, Longchamps was posted at No 609 RAF Squadron, equipped with a new, state-of-the-art fighter-bomber, the Hawker Typhoon.

The Baron’s weapon

The Typhoon was designed as a replacement for the aging Hawker Hurricane, but unfortunately, its introduction into service was quite complicated. The plane was plagued with serious project flaws that followed it throughout its career.

- Structural failure – Under severe stress, the Typhoon was prone to lose its entire tail section. RAF records show that 23 pilots lost their lives victims of this problem.

- Carbon monoxide seepage – A design flaw allowed fumes from the engine exhaust to enter the cockpit. Several improvements were made, changing the length and the curves of the tubes but the problem was never entirely solved, forcing the pilots to wear oxygen masks all the time during their missions.

- Engine wear – Poorly designed air filter allows solid particles to be swallowed by the engine, causing premature internal wear. Sending engines to a complete overhauling after only 3 missions was not uncommon.

Despite all the problems, Hawker and RAF were committed to making the Typhoon a front-line warrior. The fighter was designed to beat the Spitfire in performance and firepower. It was powered by a revolutionary 36.7-liter displacement, 24-cylinder Napier Sabre engine. This liquid-cooled power unit was designed in an “H” layout. Basically, this engine consists of two separate flat 12 engines (complete with separate crankshafts), mounted one on top of the other and geared to a common output shaft. The name “H engine” is due to the engine blocks resembling the letter “H” when viewed from the front. The Napier Sabre was capable of producing 3500 HP on the later versions. Just to give an idea, the much smaller Rolls Royce Merlin V12 that powers the Spitfire (27 liters) could crank out 1580 HP on the later versions.

The Typhoon never succeeded in surpassing the Spitfire as the RAF main fighter but all that raw power was to be put to good use. The plane proved to be a versatile platform and with some modifications, it was used as a long-range fighter, fighter bomber, and, perhaps, the role in which it performed best, ground attack.

The already formidable firepower provided by the 4 Hispano-Suiza 20mm cannons was significantly improved with the adoption of bombs and rockets, mounted under the wings. The increase in weight required a more robust landing gear, but the 24-cylinder Napier engine took it like a champion. The Typhoon blossomed into a very destructive machine.

Pummeling the Germans

The squadrons of Typhoon, alongside its American cousin, the P47 Thunderbolt, became the nightmare of the German logistics and infrastructure. Trains, truck convoys, bridges, depots, and even tanks, everything was fair game to those hunters. There was no other place Baron Longchamps would rather be than behind the controls of his Hawker Typhoon, and it didn’t take long before he proved to be a talented and aggressive pilot. The man was doing his part in the war but that was just not enough.

Longchamps was flying a British airplane and wearing the RAF uniform but his heart and mind were still in Belgium. He was constantly in contact with the resistance, in his hometown, Brussels. It was in 1942 that he received the dreadful news that his father was captured and died under torture at the hands of the Gestapo.

Longchamps couldn’t bear the idea that his father might have died during interrogation about his son, who fled to England and now was an RAF pilot. Now the only thing the young Baron had in his mind was revenge.

Thanks to his friends in the resistance, Longchamps knew that the Gestapo was using the Résidence Belvédère, a luxurious Art Deco apartment building located at 453 Avenue Louise, in downtown Brussels as its headquarters.

The rogue mission

Jean immediately started a campaign to convince his squadron leader that a raid against the Gestapo building was not only possible but highly recommended. The Baron had some good arguments in his favor: he could lead the attack since he knew the city like the back of his hand, and a blow to the Gestapo would certainly disrupt their operations, giving some room to the resistance to carry on their jobs.

At this point, the squadron commander knew that the biggest reason behind this proposal was revenge, and consequently, the raid requests were denied. The RAF resources should be applied against more important targets.

Longchamps never abandoned the idea of attacking the Gestapo headquarters, even if he had to carry on alone. Revenge is a dish better served cold.

Meanwhile, the 609 Squadron kept hammering the Nazi’s installations inside occupied France, but on January 20th, 1943, the Baron and his wingman, Flight Sergeant André Blanco, received orders to attack a rail yard near the city of Ghent, in Northwest Belgium. That was the chance he was waiting for.

He ordered his Typhoon to be armed and fueled to the max and at the scheduled time, both pilots took off towards the occupied Belgium. During the attack, Sgt Blanco noticed that Longachamps barely touched the trigger, it seemed he was saving ammo.

Upon finishing the mission, both Typhoons are heading back home when, suddenly, Longchamps storms away from the formation and before cutting off his radio, he orders his wingman to keep the course and not follow him. Blanco realized exactly what was about to happen.

Flying low and fast, Jean crosses into the city limits, and following the well-known streets of downtown, he heads straight to the Résidence Bélvedére building. On the ground, citizens and occupiers are busy with their daily routines when the stillness of the morning is broken by the furious roar of the Napier engine. The noise drew several Gestapo officials to the front windows of the building, scanning the skies, trying to identify the incoming plane. For Longchamps, this is the icing on the cake.

He starts shooting aiming at the middle of the building then he pulls the stick, graciously lifting the nose of his Typhoon, covering the rest of the facade with bullets. Inside the headquarters the hell broke loose, the destruction caused by the hail of explosive 20mm cannon shells is beyond anybody could imagine. At the top of the building, there was an anti-aircraft gun but the crew could do nothing to repel the enemy fighter. They were not prepared for this kind of attack.

The rogue Baron was not quite done with his mission, he had a bag of small Belgian flags made by Belgian refugee schoolchildren in London. After the attack, he scattered those flags across Brussels. Then he dropped a Union Jack and a large Belgian flag at the Royal Palace, in Laeken, the official residence of the Belgian royal family, and then dropped another at the garden of his niece, the Baroness de Villegas de Saint Pierre. Quite a busy morning indeed.

The aftermath.

Jean made it back to England, safe and sound. At the base, he was cheered as a hero by his comrades, but the squadron commander was not very pleased about this insubordination. As punishment for his reckless behavior, Longchamps was demoted from Flight Lieutenant to Flying Officer.

The official report from the Nazi authorities in Brussels stated that only 4 officials lost their lives as a consequence of the attack, obviously, they were downplaying the real results. According to the resistance, between 25 and 30 Gestapo personnel died, but the firing was so precise that no other building in the vicinity was hit. Among the victims there were: SS- Obersturmfuher Werner Voght, SS Sturmbannfuher Alfred Thomas, head of Abteiling III in Belgium, and a high-ranking Gestapo officer named Müller. Of course, there was retaliation, more innocent people were killed at the hands of the Gestapo, but the morale of the invaders was visibly shaken and the structure of command was disrupted for several days.

The RAF high command had no other option than recognize the valor of the mission. The man said he could strike a blow at the heart of the Nazi occupiers and he just did it.

On the day of his birthday, 31 May 1943, Jean de Selys was awarded the British Distinguished Flying Cross.

At the ceremony (pictured above), the Squadron Commander read the following:

“This Officer is a pilot of exceptional ability and keenness. He shows a great offensive spirit and is eager to engage and destroy the enemy whenever possible. He has shown his great courage and initiative in numerous rail transport and the Gestapo headquarters attack in Brussels. He has also destroyed at least one enemy aircraft and damaged another”.

The attack on the Gestapo HQ in Brussels represented much more than a strike against the Germans. More than anything else, it gave hope to the Belgians, it showed that the Allies were working hard to liberate the country.

The ground offensive to get Belgium rid of the Nazis began on 2 September 1944 with the liberation of La Galerie and was completed on 4 February 1945 with the liberation of the village of Krewinkel. The freedom came after four years of occupation.

Sadly, Longchamps didn’t survive to see his beloved country free. On 16th August 1943, after returning from a mission with No.3 Squadron over Ostend, de Selys was killed when his Typhoon Ib EJ950 QO-X crashed at Manston, during landing procedures. It is possible that the aircraft was damaged by flak. It suffered structural failure, breaking into two and crashing on approach.

He was buried at Minster Cemetery, England.

The city of Brussels erected a statue in honor of Jean de Selys Longchamps, right in front of the building he partially destroyed in 1942. It is a monument to remember the bank clerk who became a fearless fighter pilot and a national hero. The RAF airman who put his love for Belgium above his duties as a pilot.

Note of the editor: According to Marc Audrit, the author of the Longchamps biography, his father was never arrested and died peacefully in 1966. Marc goes on to say there are a lot of myths surrounding de Selys’ raid and he debunks them all in this book released in 2023. (picture below). It might be a fascinating reading.

Note of the editor – 2: A total of 3317 Hawker Typhoons were produced and just a handful of them survived the war or the crusher. There is a group of people dedicated to restoring one Thyphoon and making it airworthy again. They started with pieces and bits of a plane and the journey proved to be a hard one. You can check it at their website – https://hawkertyphoon.com/

Interesting! I am not particularly interested in aircraft but not far from where we live in the UK is RAF Cosford which includes the RAF Museum. I had a friend visit about three weeks ago who is interested in aircraft and so I took him there. You would love it! If ever you find yourself in the UK, let me know and I’ll take you there too. Free entry! https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/midlands/ Best wishes, Bob.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow!!! Thank you so much for offering to take me to the museum.

What a coincidence, a couple of days ago I was checking the RAF Museum gift shop, online. So many interesting things they have.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You need to get to AirVenture at Oshkosh where you’ll see planes like this fly. My treat

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oshkosh is on my bucket list!!! I will go for sure.

LikeLike

Fascinating story. What courage! Thanks for sharing it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am happy you enjoyed the post, Glenn.

It is always a pleasure to research and write about the less-known WWII stories.

LikeLike