This is a well-known story that has been told over and over again among the gearheads around the world. Just like any other story/legend, this one can vary widely depending on who is telling it, but it mostly goes like this:

Ferruccio Lamborghini, the founder of Lamborghini Trattori and notorious bon vivant, was dealing with a very annoying problem with the clutches of his Ferraris. After repeated trips to Maranello to have them replaced, he demanded to see Enzo Ferrari. Some say Ferrari refused to talk to him, but eventually, Lamborghini got to see the Commendatori. He looked Enzo in the eyes and said: “Ferrari, your cars are rubbish!”

The conversation went sour in the most Italian way possible when Enzo replied, “You may be able to drive a tractor, but you will never be able to handle a Ferrari properly.”

“This,” Lamborghini later said, “was the point where I finally decided to make the perfect car.”

To be fair, Ferrari was not the only flawed GT car in the early 1960s; Alfa Romeo, Mercedes, Lancia, Maserati, and Jaguar were all complicated cars, to say the least, and Ferrucio had tried them all.

In 1963, Ferruccio founded the Lamborghini Automobili with the daunting mission of building the perfect GT car, which should offer style, performance, comfort, and reliability.

Although the history of Lamborghini is much more complex and interesting, I will focus on one car specifically to show how hard it can be to make a dream leave the drawing board and become a reality.

Ferruccio was a talented mechanic and a visionary entrepreneur. The agricultural business was booming in post-war Italy, and his tractors sold like hotcakes. He was also involved in manufacturing heating and cooling equipment for residential and commercial properties. Financially speaking, Lamborghini was much more comfortable than Ferrari, which enabled him to pull some talented young people from other companies, among them Gian Paolo Dallara, Paolo Stanzani, Bob Wallace, and Giotto Bizzarrini.

Lamborghini unveiled its first car, the 350 GTV, at the 1963 Turin Auto Show (pictured above). When the team was assembling the prototype, they discovered that the Bizzarrini-designed V-12 wouldn’t fit under the hood. With no time to redesign the car, the logical solution was to remove the engine for the show, but without its weight, the car’s nose didn’t sit at the right height. The solution was to ballast the engine bay with floor tiles from the factory and keep the hood closed at the show. Lamborghini has preserved a section of the original factory floor from which the tiles were pulled.

Seriously? No one among those talented engineers and designers bothered to check the measurements of the engine and the engine bay while the whole thing was still on the drawing board. This episode shows that Lamborghini’s team was far from a professional level and this kind of jerry-rig solution would become a norm instead of an exception.

After this long but interesting introduction, we can dive into the main subject of this post.

The Lamborghini Miura

Enzo Ferrari wasn’t ashamed to say that the only purpose of producing street cars was to raise money to keep the Ferrari race team competing. Ferrucio’s idea for Lamborghini was different; he had no intentions to get involved in motorsports; he just wanted to build GT cars. Should those cars be fast? Yes, of course, but not extremely fast.

When Bizzarini created the first Lambo V-12, he was not fooling around. After all, he was getting a bonus for every horsepower over what Ferrari’s V12 could produce. The 3.5 liter, quad-camshaft, all-aluminum engine could produce 350 HP @ “mind-blowing” 9,800 rpm. This machine was, in fact, one step above the Ferrari V-12 and could have been a great Formula One engine, but to Ferruccio’s standards, it was too wild for his cars. After many disagreements, Bizzarini left the company and founded his own sports car brand.

What Bizzarini had in mind when he created the V-12 was to bring Lamborghini to the race tracks, and he was not alone in that idea. Ferruccio deserves to be praised for hiring a young team (most of them were in their late 20s) instead of an experienced team, but he was having a hard time curbing their desire to build a purebred race car.

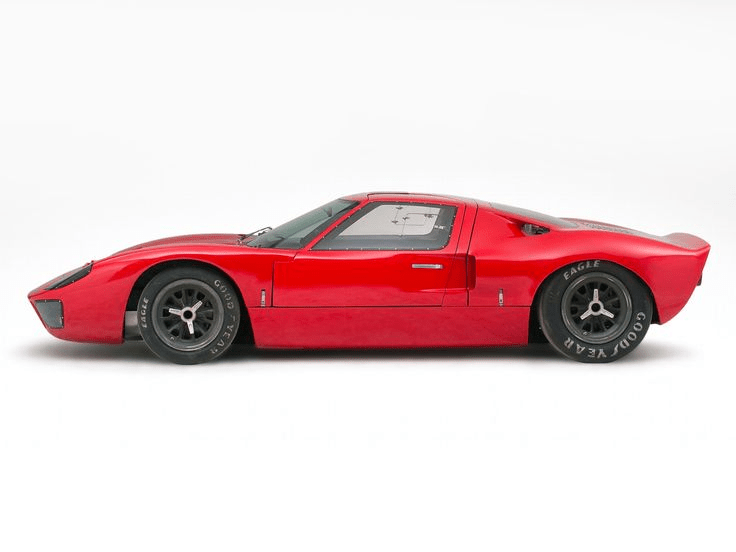

In 1964, Ford was already battling Ferrari in the Sports Prototype arena with the gorgeous GT-40, and the guys at Lamborghini were pumped up to build something similar. In 1965, Dallara, Stanzani, and Wallace began to work on a prototype called P400 (P stands for posteriori, or rear in English and 400 means 4-litre engine) during their spare time, mostly at night. The idea was to produce a street-legal sports car that could perform superbly on the race tracks—a unique car that could change Ferruccio’s mind about creating the Lamborghini race team.

Ferruccio didn’t mind the enthusiasm of his boys and encouraged them to continue their development. However, he didn’t promise to put the car into production; he viewed this new prototype as a good advertising stunt, similar to a concept car.

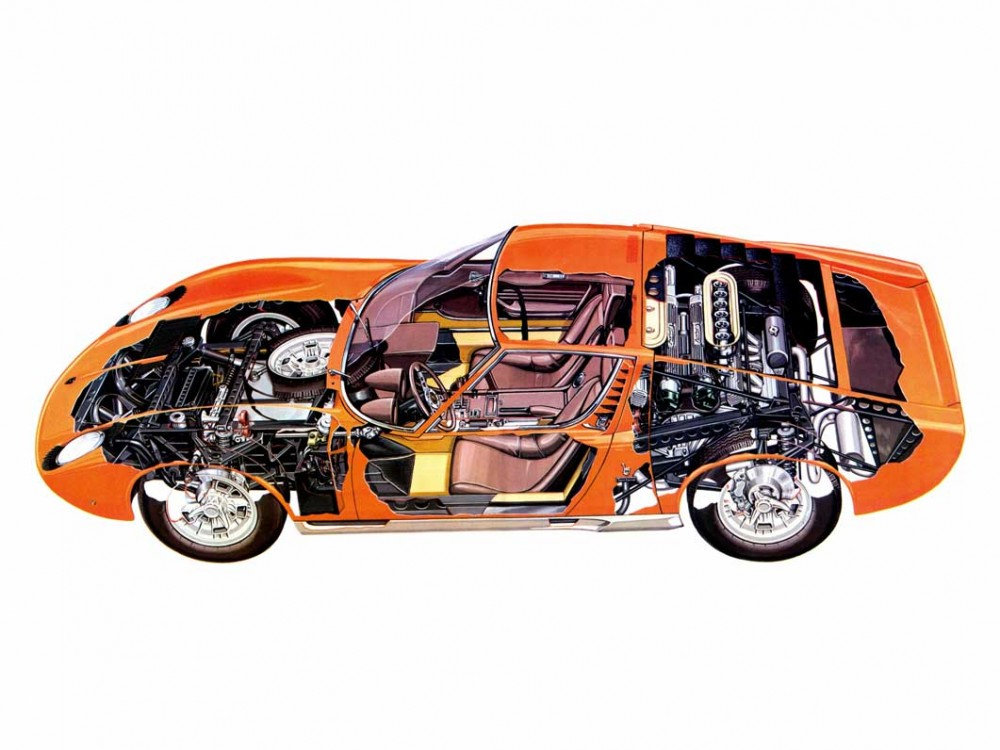

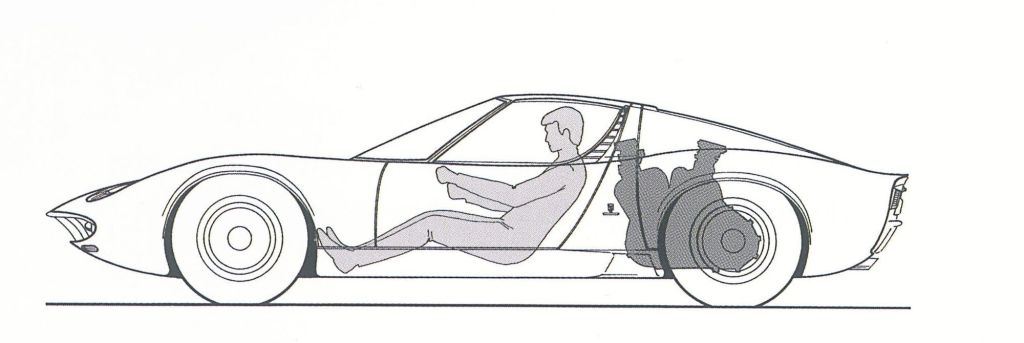

The first challenge was to fit the massive Lambo engine into such a diminutive car. With 42 inches long, it would be impossible to install the V-12 in the mid-engine position. After some consideration, the team devised an ingenious solution: they rotated the engine 90 degrees and positioned it on top of the transmission, just like the Brits did with the Mini. The casting for this engine/transmission package proved to be highly complex, mainly because the rear differential should also be part of it.

The P400 drive train is a magnificent piece of machinery (photo above); it is 1960s Italian engineering at its best.

Dallara used his expertise as a former aeronautical engineer to develop a beautiful steel chassis around the drive train.

The team got the rolling chassis done in time for the 1965 Turin Auto Show, and it attracted much more attention than the regular production Lamborghini GT cars displayed there.

The visitors and media were amazed at how the Lamborghini team enveloped the engine and transmission so neatly into the chassis. The transverse, mid-ship position of the drive train was quite unusual at the time, and everybody at the show was thrilled with the idea of such a small and lightweight car powered by an enormous V-12.

By the end of the show, more than ten customers had already made a down payment to secure a new P400, even without knowing what the body would look like.

Ferruccio was in a pickle; the rolling chassis that his boys created during their off-time sold better than all of his beloved GT cars together. The boss congratulated the team and gave them the green light to prepare the assembly line as fast as possible because 10-plus customers were waiting for the P400.

Dressing the beast

Design is one of the most important chapters of a car’s development, but when we are talking about an Italian sports car, then the significance of design becomes paramount.

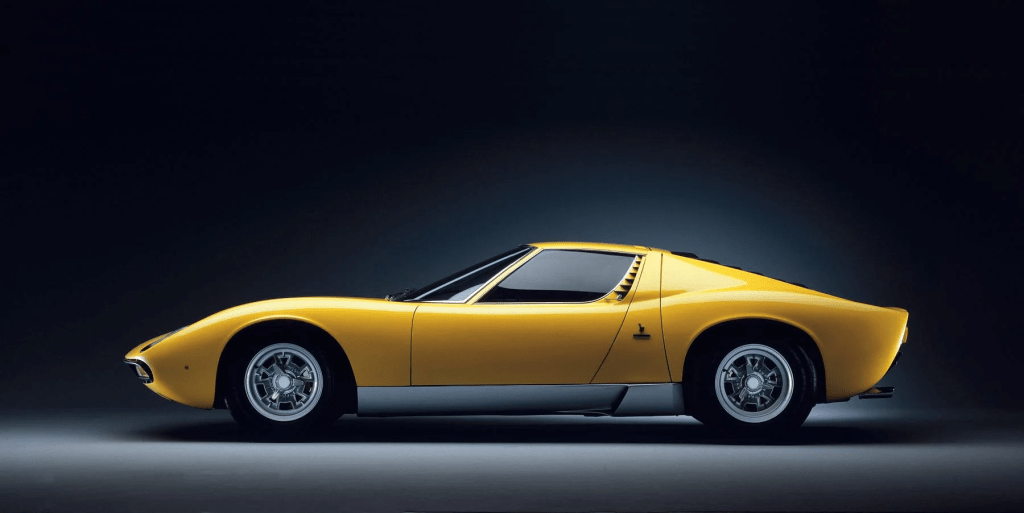

Ferruccio wanted to hire a design studio with no ties to either Ferrari or Maserati. He invited Giuseppe ‘Nuccio’ Bertone, the boss of Bertone Studio, to examine the rolling chassis. Bertone accepted the challenge to create a stunning body for the car in record time for the 1966 Geneva Auto Show. The chassis was brought to Bertone’s Stile Department, and the task was given to another young talent, the 27-year-old Marcello Gandini, who had recently replaced the famous Giorgetto Giugiaro as the head of the design department.

Gandini and his team worked day and night to fit the bodywork to the innovative platform. Under the guidance of Nuccio Bertone, they successfully completed the project in just two months. It’s truly unique that they went from the first sketches to the running prototype in such a short time! Nuccio Bertone drove the car from Caprie to Geneva the night before the show opened.

The Miura was born

Ferruccio named the car Miura, after a Spanish fighting bull breed, in honor of Lamborghini’s recently created logo.

Gandini had created a masterpiece, one of the most beautiful sports cars in history. The design of the Miura is simple and clean, with a traditional appeal of the 1960s with a long nose and short rear deck.

It is inevitable to compare the Miura with the car that, according to some scholars, serves as inspiration: the Ford GT-40. The GT-40 was created as a purebred competition machine but could have easily become a street-legal sports car.

Both cars have curvaceous, sensual, feminine lines, a trademark of the 1960s, known as the most romantic period in sports car history. The Miura was originally designed as a street car, but the team also wanted to see it on the race tracks.

As was expected, the Miura was the star of the 1966 Geneva Auto Show, and at the end of the event, another 30 customers had made the down payment for the car.

Miura P400 especs.

Engine: Lamborghini V-12, 4 litres, quad-cam, all-aluminum. Rated at 320HP

Transmission: 5-speed manual

Weight: 1,125 kg (2,480 lbs)

Wheelbase: 2,500mm (98 inches)

High: 1,060mm (42 inches) – only 2 inches higher than the GT-40.

With a top speed of 280 km/h and an acceleration of 0 to 100 km/h around 6 seconds, the Lamborghini Miura was the fastest “production” car in the market. For the first time in history, the automotive media used the term supercar to describe the Miura.

A nightmarish sports car.

Everything was happening too fast; the Miura jumped from the drawing board to the production line in less than a year. Ferruccio, hoping to boost Lamborghini’s sales, gladly accepted orders for a car that hadn’t even gone through extensive trials and road tests.

The Miura proved to be a very problematic car, an absolute nightmare for the owners—precisely the opposite of the hassle-free car Ferruccio wanted to build.

Here is a list of the issues:

- The chassis created by Dallara was a work of art, but it was not very stiff. The body, made of thin steel sheets (doors and center section) and aluminum (front and rear sections), didn’t provide much support either. The first generation of the Miura was a very flimsy car. Some structural reinforcements were later added, but the problem was never entirely solved.

- During the development, the team adapted the same front and rear suspensions used on the front-engine Lamborghini GT cars, and the result was not so good. Muira’s handling is somehow poor when compared with Ferrari and Maserati.

- The Miura was fast but dangerous. The design of the front end allows a substantial amount of air to flow underneath the car at high speeds, creating a frightening sensation as though the car is about to take off.

- The innovative idea of having the engine and transmission housed in the same case means they also share the same oil. While this design solved the issue of limited space for the drive train, it also gave rise to a new problem: oil starvation. During long turns at high speeds, copious amount of oil would shift to one side, leading to engine seizures.

- But the most alarming issue with the Miura was its tendency to catch on fire. The Lamborghini V-12 engine was equipped with four triple-barrel, downdraft Weber carburetors that were dangerously positioned over the spark plugs. If the carburetor floats failed or if there was contamination in the needle and seat, combined with high fuel pressure, it could result in gasoline spilling over the ignition components and causing a fire. Owners and mechanics took measures to prevent their cars from being destroyed, such as using trays at the base of the carburetors and installing fire extinguisher systems. However, despite these precautions, many Miuras were lost due to fires.

Ferruccio knew all these unsolved problems would soon torment the owners, so he concentrated the sales in Italy, making it easy to bring the cars back to Lamborghini for repairs.

There are stories of Ferrucio taking customers to long lunches and dinners to appease their ire, while their cars were being repaired. At this time, Lamborghini was far from being a well-established car company, with no more than 80 employees on the payroll. They desperately needed the Miura to succeed.

In 1967, Ferruccio reached his limit. Automobili Lamborghini was not heading in the direction he had always wanted, and although the Miura would soon receive the necessary improvements, he was frustrated with all the car’s problems. Instead of shutting down the company, he removed himself from his position and promoted Paolo Stanzani as the head of Lamborghini.

Stanzani accepted the new position but not without some conditions. This is what he demanded:

“You are the boss of the company, I know that. However, you will not come and create dissent, override me in front of people, or put your nose in things. Understand that you can ask me anything but speak only with me.”

P400S

In 1968, with Stanzani as the company’s captain, Lamborghini released the Miura P400S with some very welcomed updates. The chassis received structural reinforcements; front and rear suspensions were revised, and larger tires were adopted, considerably improving the car’s handling.

Interior comfort was traditionally neglected in Italian sports cars of the 1960s but the Miura should be different; the P400S was equipped with power windows, and air conditioning systems was optional.

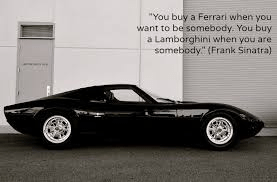

The P400S propelled the “popularity” of the Miura around the world. Frank Sinatra bought one in 1969. Former factory Sales Manager Signore Ubaldo Sgarzi recalls Sinatra’s unannounced visit to the factory, with a specific request for no publicity; Signore Sgarzi gave Sinatra a tour of the Sant ‘Agata works. The car, with chassis #4407, was painted in Arancio Metallico and trimmed with wild boar skin leather and orange shagpile carpeting – orange was Sinatra’s favorite color. The dispatch date is recorded as 12/12/69, Sinatra’s 54th birthday! The car survived these days; after changing owners a few times, the Miura was auctioned in 2003 and now belongs to a collector.

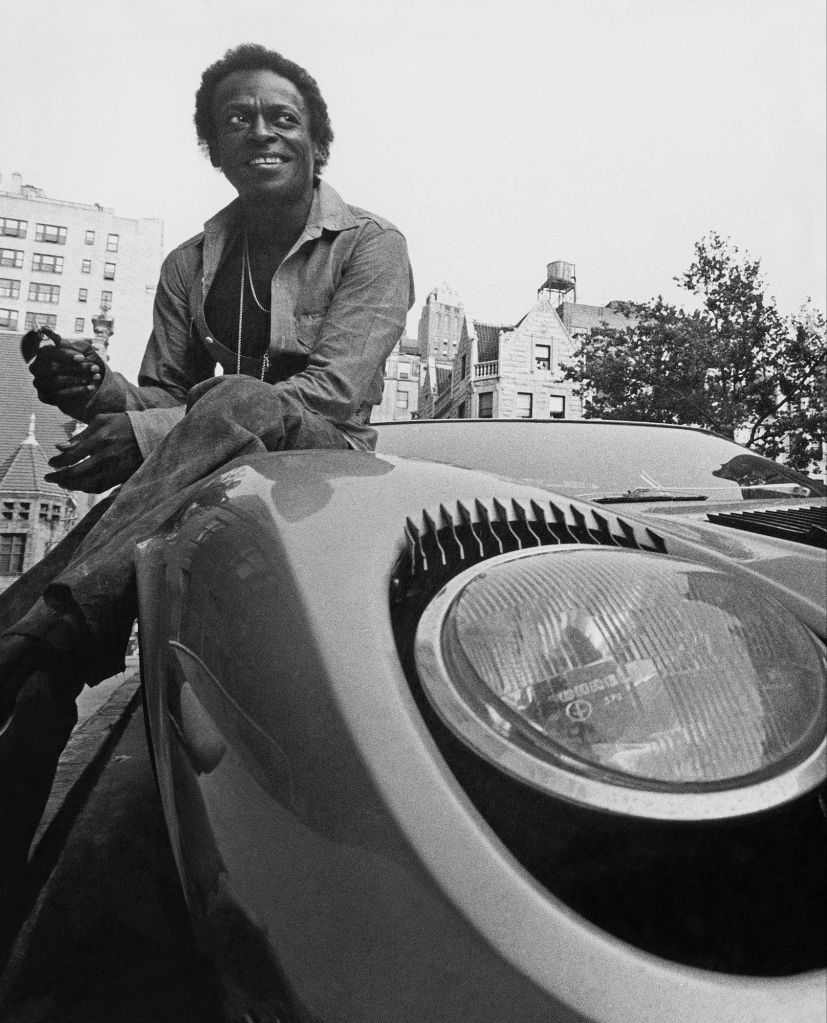

The Jazz legend Miles Davis also owned a Miura, but he crashed the car while driving under the influence of narcotics. Davis supposedly fell asleep at the wheel and totalled his car. He was taken to the hospital with both ankles broken and released the following day. As soon as he recovered from his injuries, he bought another P400S.

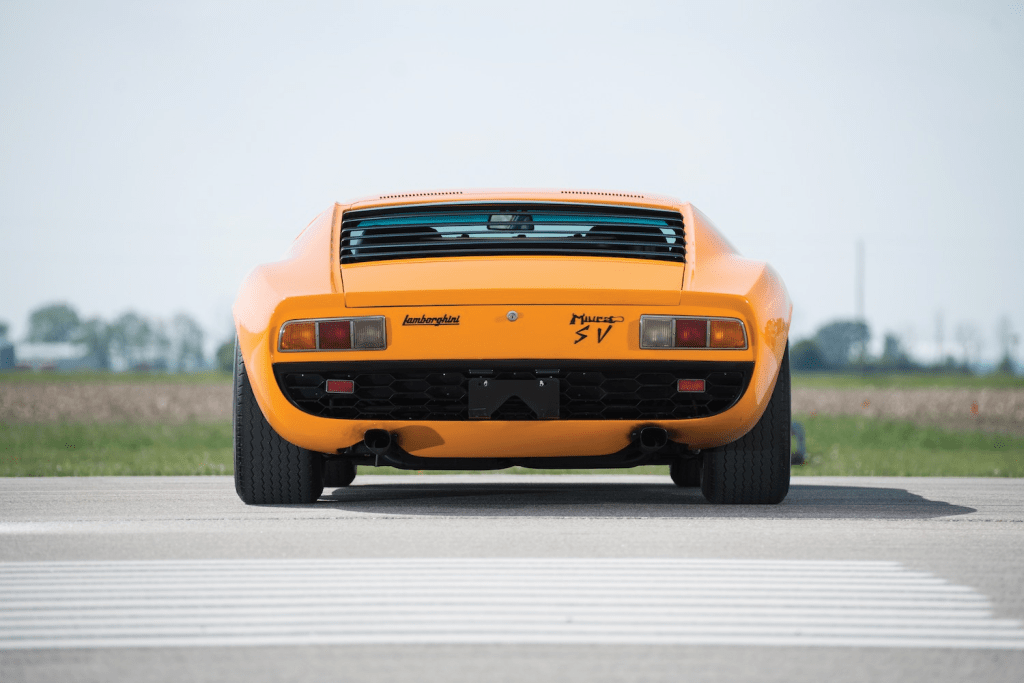

P400SV

In 1971, Lamborghini unveiled the ultimate version of the Miura, the P400SV.

The most significant changes were related to the drivetrain. The gearbox now had its lubrication system separate from the engine, which prevented annoying engine seizures. The company claimed that improvements on carbs and camshafts increased power output to 385 HP. However, Bob Wallace, the New Zealander responsible for overseeing engine production, later said that these “improvements” never happened. The Miura’s V-12 always produced between 320 and 330 HP throughout its eight years of production.

The SV has wider rear fenders to accommodate the new 9-inch rear wheels. The car came equipped with Pirelli Cinturato 215/70 R15 front and 255/60 R15 rear tires.

One of the distinctive features of the Miura is the famous “eyelashes” around the headlights, which were removed on the SV model, making it easier to differentiate the car.

1973 was the last year of production of the Miura. Its gorgeous body style had no place in the 1970s, a decade that became known for its weird, angular design concepts.

Just like any other Italian exotic super-car of that time, the Miura was produced in very limited numbers:

Miura P400 – 1966 to 1967 – 474 units

Miura S – 1968 to 1970 – 140 units

Miura SV – 1971 to 1973 – 150 units

Bob Wallace just couldn’t help himself and eventually built a single racing prototype based on the P400SV called “Jota.” The car was sold to a private racer in April 1971. The new owner crashed it on the yet-unopened ring road around the city of Brescia, and… you guessed it, the Jota burned to the ground. There are a couple of recreations of the car around the world, like the one pictured above.

Life after the Miura

Controversial, groundbreaking, problematic, and legendary, the Miura was the car that Ferruccio never wanted to build. Still, at the same time, the car made Lamborghini what it is today. Without it, the company wouldn’t be more than a footnote in automotive history.

The partnership between Stanzani and Bertone continued, and together, they created a worthy successor for the Miura, the Countach. (Not my cup of tea, though).

Lamborghini was never profitable at that time. The company went through various owners – questionable deals with Ferruccio’s personal friends, shady foreign business people, a handful of bankruptcies, and even the Italian government. In 1987, Chrysler bought the company and kept it alive for many years.

It was under Chrysler’s ownership that Lamborghini ventured into Formula One, the company supplied engines (V-12, of course) for Larrousse (1989–1990, 1992–1993), Lotus (1990), Ligier (1991), Minardi (1992). Lamborghini even had its own official team in 1991, although under a different name, Modena.

Automobili Lamborghini was acquired by Volkswagen in 1998 and became its third luxury brand alongside Bentley and Bugatti. The Germans, as expected, put some order in the house, and Lamborghini finally became profitable and successful.

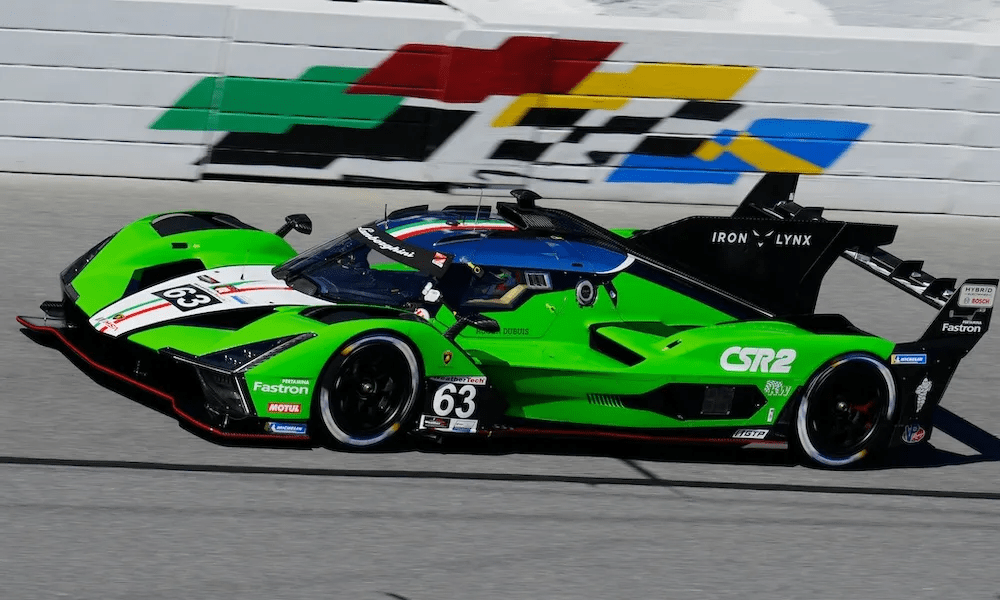

In 2024, Lamborghini introduced the SC63 Hybrid (shown above) in the Hypercar class, the highest category in the FIA World Endurance Championship. The car will compete against formidable opponents, including their longtime rival, Ferrari.

Feeling generous? Visit my “Buy me a Coffee” page.

Oh my goodness Rubens … I can’t believe the amount of research you must have done for this article. This must have taken you weeks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are right, Brother, it took me around 3 weeks to get this article done. It is the typical case of “one thing leads to another” and everything about Lamborghini and the Miura is interesting, making it hard to leave any detail behind.

But it is always a pleasure to write about the stuff we love.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, those details about the Miura are interesting. For example, despite being a car guy, I never saw the resemblance between the GT40 and the Miura until you put those two side-view photos nest to one another. I guess in my mind, they were both mid-60s GT cars and that was the style of the era. Nope… those cars are almost twins.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating story

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Glenn. The story of the Miura is one of the most interesting in the automotive universe.

LikeLike

Fantastic article! The Miura is a truly beautiful car. You’ve pulled together some amazing photos as well. Really well done!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Stuart. The car is truly beautiful. Fortunately, there are countless pictures of it available on the internet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Miura was an amazing set of wheels for the 1960s even though it had problems. But then, what car didn’t have problems back then? The Italians seem to have a natural gift for style regardless of what it is they’re creating. Great car bios, Rubens! 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Nancy.

There was a great automotive reporter in Brazil, his name was Spedito Marazzi; he used to say this about Italian Sports cars: They cost a fortune to buy and twice as much to keep. They are noisy, hot in the summer, and cold in the winter, and eventually, you will become so close to your mechanic to the point of inviting him to be the godfather of your kids.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha ha! Good story, Rubens, because it has a good foundation of truth behind it. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person