In the world of motorsport, evolution is constant. If you were to compare a Formula One car from the 1970s to a modern one from the 2020s, the differences due to half a century of technological advances are simply astonishing. However, both vehicles still share some core similarities, such as having four open wheels, a mid-ship engine, and the assistance of aerodynamic components.

But the creative minds of engineers and designers never rest, and occasionally, someone tries to break free from the core concept that defines what a race car should be.

If you ask any gearhead: “What is the craziest race car that ever competed in motorsport?” I bet 9 out of 10 answers will be: “The 6-wheeled Tyrrel, from the 1970s.”

In fact, the Tyrrel P-34 was the most popular unorthodox race car that ever hit the race tracks. It competed for only two seasons, 1976 and 1977, but that was enough to make it unforgettable.

It looks like a jet fighter

In a more recent era, another ambitious and innovative race car deserves to be remembered, mainly because it never reached the popularity of the Tyrrell P34: the incredible Panoz/Nissan DeltaWing.

The creator of this project is the British race car designer and engineer Ben Bowlby. He is the leading character of this story, a lateral thinker and the leader of his team. Bowlby based his concept on the idea that a much narrower front facia can immensely improve its aerodynamics and make the car a lot lighter.

The first real opportunity for Bowlby to see his project become a reality came in 2009 when Chip Ganassi saw it as an attractive new car for the F-Indy. At this time, Formula One and WEC were trying new and revolutionary designs for their vehicles, and F-Indy was slowly opening its doors for something similar. To make the project become a reality, a consortium was assembled: Chip Ganassi Racing, Dan Gurney and his All American Racers team, Duncan Dayton of Highcroft Racing, and Panoz, which was the company that actually built the prototype. The car was presented at the 2010 Chicago Auto Show, and needless to say, the Delta Wing was a success among the visitors. (Picture above)

According to the initial tests, the Delta Wing proved slightly faster on straight and corner speeds than a 2009 Dallara IndyCar on both ovals and road/street courses with half as much weight, engine power and fuel consumption. The original prototype measured an unusually narrow 2.0 feet (61 cm) front track and a more traditional 1.7 meters (5 ft 7 in) rear track. The downforce comes from air passages on the car’s underbody, eliminating the need for front and rear wings.

Panoz used a chopped Aston-Martin LPM1 chassis to build the car, and it was powered by a 300 hp, four-cylinder, turbocharged Chevy engine assembled by Ray Mallock Engineering.

The Delta Wing was scheduled to debut for the 2012 season, giving the team time for the necessary tests and improvements. Unfortunately, the car proved too radical for F-Indy, and Chip Ganassi decided to use a more conservative project from Dallara.

Next stop: Europe

Bowlby didn’t give up when F-Indy closed its doors on the Delta Wing. Instead, he presented his project to the World Endurance Championship (WEC) in Europe and quickly received an invitation to compete in the Garage 56, an experimental class of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, for the 2012 edition.

The WEC is a place where automakers pour a considerable amount of money to have a spot on the grid; if Bowlby wants to make a splash, he would need a few heavy-weight partners. The first one to jump into the wagon was Michelin; the French tire company fell in love with the Delta Wing and promised to produce the exclusive tires for the car, according to the specifications from Bowlby and Panoz.

Nissan comes on board

The next step in this endeavour was to find an engine supplier with deep pockets, willing not only to provide the drivetrain but also help in developing the entire car and contribute to the costs of participating in Le Mans.

Rumor has it that Michelin insisted on having a French automaker as a partner, and Renault initially answered the call. The only problem was that they were already deeply involved in F-One, and the company’s CEOs decided to pass the project to their Japanese partner, Nissan.

With little tradition in motorsport and not very keen on revolutionary projects, Nissan reluctantly accepted the challenge. The company provided a 1.6-liter, four-cylinder, turbocharged engine found in the Nismo version of the Nissan Juke, capable of producing 350 hp.

Even if the car was being initially developed in the USA, the North America Nissan was not involved in the project. At the Delta Wing’s first test, at Buttonwillow in the California desert in March of 2012, Nissan of Europe brought a few engines, a couple of drivers, and a handful of engineers. They were so concerned about the Delta Wing crashing on the first turn that they de-badged the engines, put all their employees in plain clothes, taped over logos, and denied all involvement.

At the end of the day, the car performed quite well and Nissan felt confident to apply its logo all over it.

Since the Delta Wing would be competing under the experimental Garage 56 (racing for technological advancement, not for points and glory), there was no minimum weight rule to follow, and the team took full advantage of this. Each 4-inch-wide and 23-inch-tall front wheel and tires can be lifted with a finger, literally. The front brake rotors are the same size as those found on mopeds (keep in mind that most of the breaking goes to the rear axle). The team even gave up on the 6-speed transmission for a 5-speed just because it was lighter.

In full race trim, the car checked at just under 1,100 pounds; by comparison, the weight of the 2011 Le Mans-winning Audi R18 TDi was nearly 2,000 pounds.

Ready for Le Mans

The Delta Wing was received with mixed feelings at the La Sarthe circuit. Some people saw the car as exciting and thought-provoking, but others saw it as a laughable, toy-like car.

Among the naysayers, the biggest puzzle was: “How can those tinny front wheels steer the car at high speed?” But guess what? They can. It is the same principle used in drag racing: those tinny front wheels on a top fuel dragster are functional, and they are enough to keep a 10,000-hp beast on the track. It is physics, baby.

On their side, the team believed that a lighter car, powered by a small displacement engine, would give them the advantage of fewer pit stops during the race.

Nissan hired three excellent drivers but they had little experience on long duration races : Marino Franchitti (Scotland), Michael Krumm (Germany), and Satoshi Motoyama (Japan). The team was afraid that the drivers would not qualify during the night trials but to everyones relief, they did. On the day before the start of the race, Bowlby was optimistic:

– “We might surprise some people. We know the car can be very fast, we know it is very efficient and we know it races extremely well in traffic amongst other cars.“-

Darren Cox, the general manager of Nissan Europe, was also excited:

–“The Delta Wing is the most innovative and ground-breaking motorsport concept of its generation. The team aims to complete the famous endurance race using half the fuel and half the tire material of a conventional LMP race car.”-

Nissan wasn’t shy anymore trying to associate itself with the project. They brought hundreds of “extra” journalists to Le Mans, and immediately the Delta Wing became the star of the show.

For a revolutionary car that was developed in such a short period, the Delta Wing was performing surprisingly well in the race. Even with constant gearbox hiccups, the drivers were clocking solid lap times, just 1 sec below the LMP2 prototypes.

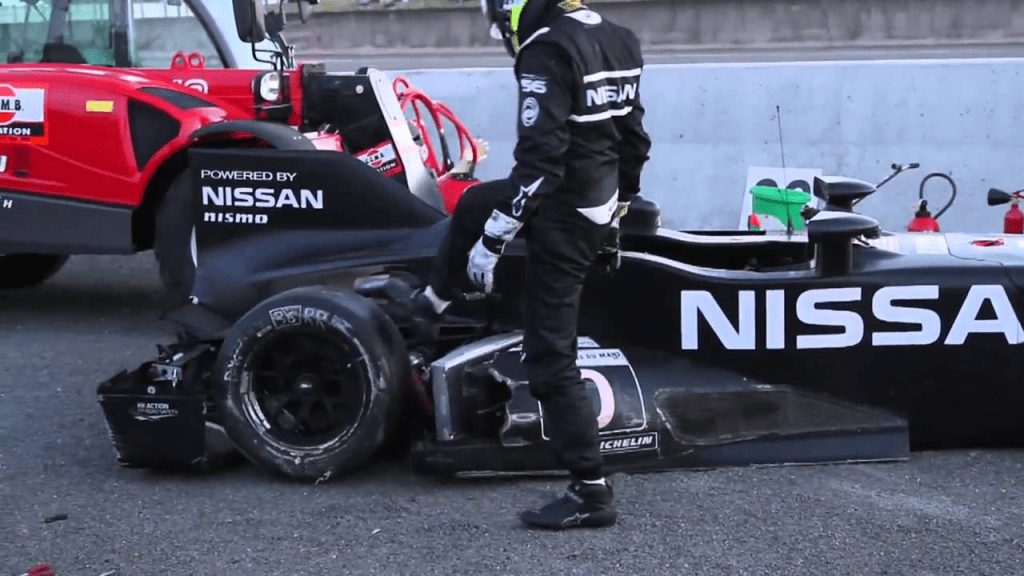

The Delta Wing made past the first 6 hours of the race, and the team was thrilled, but all that happiness wouldn’t last much longer. Nakajima, driving the #7 Toyota LMP1, pushed the Delta Wing off the track while trying to avoid slower traffic ahead, and Satoshi Motoyama crashed the Nissan prototype against the barrier.

According to the rules, a driver can try to make his car mobile again and drive it to the pits, but he must do it on his own. Motoyama attempted to repair the Delta Wing using the tools handed to him through the fence, but after more than 90 minutes, the tenacious Japanese driver gave up in tears.

The team left Le Mans with the bitter taste of defeat in their mouths, but in fact, their performance was superb. The Delta Wing was consistently clocking good lap times, and if the crash hadn’t happened (assuming the car would hold itself together throughout the race), it should have finished among the top LMP2 cars while burning half the fuel. Not too shabby for a project that Bowlby himself qualified as “incomplete.”

The next challenge for the Delta Wing was the 10 hours of Road Atlanta of 2012. The other teams shifted the way they saw the car; from a laughing stock at the beginning of the year, it became an “unfair.” competitor. The team had to follow unique rules, imposed to make the other teams happy.

For instance, the Deltawing had to start from the pit and could not start at the front of the field under full course yellow. Despite the obstacles, the team finished in fifth place overall. Driver Lucas Ordonez lamented that the restrictions and regulations prevented him from fighting for P1.

The shattered dream.

The alliance between Bowlby, Panoz, and Nissan began to crack just when the Delta Wing was at its top.

Bowlby believed that he had accomplished his mission. He demonstrated that his idea worked as he had predicted and hoped that the Delta Wing would motivate other engineers to think creatively. He was now ready for a new challenge.

Don Panoz saw the moment in a totally different way; he was the one who invested heavily to make the Delta Wing a reality, and now he wanted to make some money supplying the car to other teams. Bowlby was the father of the project, but Panoz owned the intellectual property of it. At this point; Don didn’t need Bowlby’s approval to turn the Delta Wing into a commercial success.

Nissan was in an uncomfortable position; they supplied the engine that powered the car at Le Mans and Atlanta (and a lot of stickers, too), but that wasn’t enough to claim any right to the project. Nissan knew that Panoz wanted to cut ties with them, giving their customers the freedom to choose whatever powertrain they wanted. As one could easily predict, this divorce was just about to turn sour.

Nissan managed to hire Bowlby as Director of Motorsport Innovation, and together, they created a closed cockpit version of the Delta Wing, called Nissan ZEOD RC (zero emission on demand – race car), powered by a hybrid powertrain.

The ZEOD had a much better performance and fuel efficiency than the original Delta Wing. Nissan entered the car in the 2014 24 Hours of Le Mans, and during practice, the car consistently reached 300 km/h plus going down the Mulsanne Straight. During the race, the ZEOD even completed a lap using only electric power.

Unfortunately, the car didn’t live up to expectations; the gearbox failed on lap 5, forcing its retirement.

The ZEOD project seemed promising, and Nissan wanted to expand it to the streets. A couple months after the release of the racing model, the company unveiled a small Delta Wing urban car with similar hybrid technology called Blade Glider.

Don Panoz couldn’t believe that Nissan had spent so much money and effort on a project with a design that belonged to someone else. Just a day after Nissan unveiled the Blade Glider, Panoz filed a lawsuit naming Ben Bowlby, Darren Cox, Nissan Motor Co. Ltd., Nissan Motorsports International Co. Ltd., Nissan International S.A, and Nissan North America Inc. as defendants.

The court battle dragged on until 2016 when both parties reached an agreement, and that was the end of the Nissan badged Delta Wing.

Final thoughts

2016 was also the last year the DeltaWing hit the race track (picture above). Panoz kept the dream alive for as long as he could, racing the car in the Petit Le Mans North American league and IMSA, but the lack of interest from other teams forced them to abandon the concept.

Don Panoz was passionate about the Delta Wing, but he had to come to terms with its demise. He invested a considerable amount of money to transform it into a successful race car, but money was never a problem for him. However, the world of motorsport can be quite traditional, and not all unconventional ideas are entirely accepted.

According to some sources, Nissan had the chance to acquire the rights to the Delta Wing from Panoz for $60 million, but instead, they chose to have it for free. The company missed out on the opportunity to have a truly groundbreaking urban car, but it’s unclear whether customers would have embraced it.

After leaving Nissan in 2017, Ben Bowlby returned to the UK and became involved in numerous other racing projects. There are rumors that he can not visit Georgia, USA, the home state of Panoz, due to pending criminal charges.

In the pits, nobody felt sad to see the Delta Wing gone. It always raced under the #0 as an experimental car, and as such, it didn’t have to obey strict rules like the other prototypes. It was unfair to the other teams, even though the Delta Wing never won a race.

Are there any survival cars? You bet. The chassis #003 can be seen hanging on a wall at the Panoz headquarters in Georgia, and a complete car (chassis #001) was up for sale in 2018 for $375,000. (Picture above).

Thank you for the detailed backstory of the Tyrrell P34 and the Panoz/Nissan DeltaWing race cars. The innovation was just amazing. Incredible engineering and forethought about the tiniest bit of weight. So, I would guess-as someone who knows next to nothing about race car driving-they would prefer to have teeny tiny drivers. 🙂

LikeLike

That is a good point, I wonder if the team ever considered hiring horse jockeys as race drivers.

Thanks for stopping by.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember the original Delta Wing design as the potential ‘new’ IndyCar, but wasn’t surprised when the series stuck with a traditional open wheeler from Dallara.

.

But I was really intrigued by what it might do in endurance racing. Better aero, smaller engine, fewer pit stops. Unless the ACO made unique rules to minimize its advantages (like a timy fuel cell, requiring more frequent pit stops) I was comvjnced it would win at LeMans.

.

My son Daniel and I did get to see it race at Mosport as part of the IMSA series, and the car was so loved by the wrowd…but not the other teams who saw it as athreat to the establishment.

.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice picture, Chris.

Is she Katherine Legge? During my research she appears as one of the Delta Wing drivers for the 2013 season.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s right…former Champ Car driver, current IndyCar driver and experienced sports car driver Katherine Legge was the driver, and I think the picture was from 2015 or 2016.

.

I think they had a rotating lineup of drivers, which tends to happen in LMP2 and similar.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting. I love outside the box thinking. I wish it hadn’t been shut down.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It would be interesting to observe the performance of this car after a few more years of development. I wonder what the creator is currently working on.

LikeLiked by 1 person