Even if you are not interested in military history, chances are that you have heard something about a soldier or a civilian who, miraculously, escaped from the chains of a communist regime and started a much better life in the Western hemisphere. History records numerous accounts like this, especially during the Cold War. Although every single defector had many reasons which led to such a perilous decision to escape, one reason is undoubtedly at the top of any list: life in a communist country during those days was terrible, and one could easily be lured by the prospect of an abundant life in Western Europe or in the USA. Every story has its fair share of disillusionment and courage, but some stand out for the bold actions of the defectors.

Free countries on the other side of the Iron Curtain were more than happy to receive deserters and help them start a new life. In exchange, the governments used them as propaganda, showcasing the world how our system was significantly better than theirs.

Although all “traitors,” soldiers, civilians, and diplomats were received with open arms, military personnel were the favorite of the bunch. They could provide valuable information about operations, technologies, equipment, and other relevant details about the enemy. But every now and then, a defector would bring something much more interesting than just information.

The defector

Viktor Ivanovich Belenko could have been a poster child for the perfect Soviet youth. He was born in Nalchik, the capital of Kabardino-Balkaria, USSR, on February 15, 1947. Born into proletarian poverty, he had worked himself up through the Air Force and party ranks. At the age of 29, Lieutenant Belenko was already a respected pilot in the Air Defence Forces, a branch separate from the Soviet Air Force and arguably more prestigious. He was stationed at Chuguyevka Air Base in the Soviet Far East, close to Vladivostok.

A fighter pilot in any Western country would likely have enjoyed a decent and fulfilling life; however, that was not the case behind the Iron Curtain. At that time, conditions at the airbase were grim, characterized by inadequate facilities and low morale. Belenko tried to address these issues with his superiors, but he was essentially ignored and ridiculed. To make matters worse, his wife had grown weary of life as a military spouse and filed for divorce. Disillusioned with his circumstances, Belenko decided it was time to leave.

The machine

Fueled more by fear than common sense, allied countries usually grossly overestimated the Soviet Union’s capabilities. From the number of soldiers ready to invade Europe to access to aerospace technologies, everything behind the curtain looked scarier than reality.

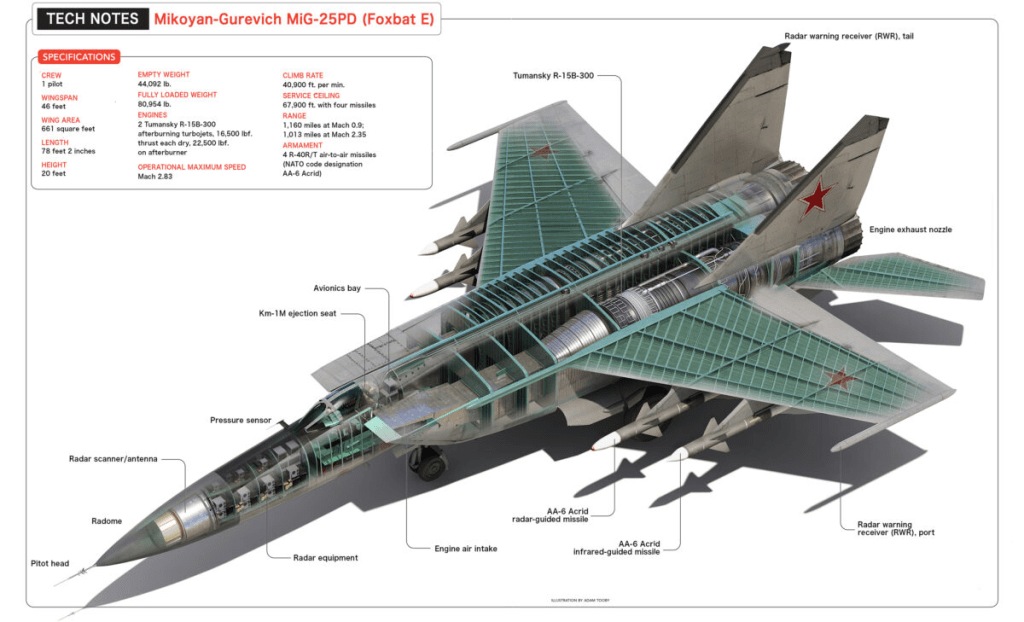

When the Soviets put the new Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-25 supersonic interceptor into service in 1969, Western analysts went crazy. The plane quickly established world records in speed and altitude and was immediately considered the most dangerous threat to NATO aircraft. The Secretary of the Air Force, Robert Seamans, had said the MiG-25 was “probably the best interceptor in production in the world today.”

The MiG-25 was code-named “Foxbat” by NATO. It is equipped with two Soyuz Tumansky R-15BD turbojet engines, capable of producing 8,790 kg of dry thrust and 11,190 kg of thrust in afterburner. The only armament was four R-40 air-to-air missiles. The Foxbat was capable of reaching a maximum speed of Mach 3.2, and a ceiling of 27 km (89,000 ft). Although the maximum speed was exceptional, the plane was unable to sustain it during combat. A limit of Mach 2.83 had to be imposed as the engines tended to overspeed and overheat at higher airspeeds, possibly damaging them beyond repair.

The scape

Lieutenant Belenko was learning to fly the new Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-25 at the time. He knew the jet fighter was a mystery to NATO, and he could use one of them as a bargaining chip in exchange for asylum. The opportunity to put his plan into action came on Sept. 6, 1976. The weather was clear, and his squadron was ready to take off on a training sortie.

The Foxbat was a voracious fuel consumer, and Belenko wouldn’t be able to fly to an American or Canadian air base. Still, he could try reaching a much closer allied country, Japan.

But it would not be an easy escape. The squadron that day would fire rockets; so, too, would a group of MiG-23s from other bases. They could easily shoot him down if his intention were evident. Another factor to consider was that clouds were starting to move in around Japan. During the pre-flight medical examination, Belenko was visibly nervous, and his blood pressure was slightly elevated. He lied to the doctor, claiming he was doing physical exercises, and the doctor believed him.

He took off on a perfect, cloudless day and joined his squadron in formation. He followed the mission instructions perfectly; however, at the far edge of the route, he didn’t circle back as per the flight plan. Instead, he continued onward, allowing the plane to gradually descend to 19,000 feet. Suddenly, the Lieutenant threw the Foxbat into a steep dive, plummeting down to just 100 feet, and kept the jet at low altitude, staying beneath radar detection.

The other pilots in his squadron chased after him, but Belenko had a good lead. He flew low and fast, at one point pulling up to avoid being hit by waves, as he invaded the Japanese airspace.

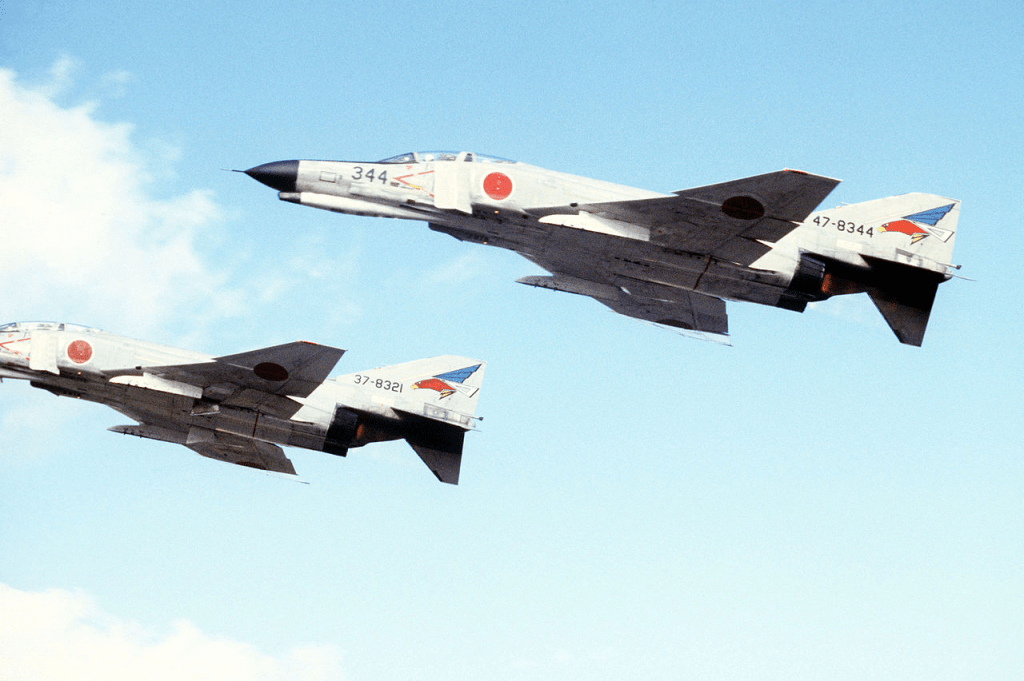

He hoped to reach Chitose Air Base, but his plane was dangerously low in fuel. At 1:10PM, Japanese radar detected Belenko’s plane, and at around 1:20PM, two F-4EJ fighters from Chitose Air Base took off to intercept the intruder.

As Belenko would admit, years later, that day was his lucky day. It was very cloudy in Hakodate, making it difficult for the F4 pilots (picture above) to spot the MiG.

Miraculously, he found the Hakodate airport, and as he started to approach, a civilian Boeing 727 was taking off, straight towards the Foxbat. Here is an excerpt from the book “MiG Pilot” by John Baron:

“He jerked the MiG into the tightest turn of which it was capable, allowed the 727 to clear, dived at a dangerously sharp angle, and touched the runway at 220 knots. As he deployed the drag chute and repeatedly slammed down the brake pedal, the MiG bucked, bridled, and vibrated, as if it were going to come apart. Tires burning, it screeched and skidded down the runway, slowing but not stopping. It ran off the north end of the field, knocked down a pole, plowed over a second and finally stopped a few feet from a large antenna 800 feet off the runway. The front tire had blown, but that was all.“

When the MiG finally stopped, over the grass, Lieutenant Belenko jumped out of the cockpit, fired his pistol into the air and shouted to the emergency crew that had just arrived: “I want to defect”. Even if the Japanese personnel didn’t understand what he was saying, they understood what was happening.

In the end, Belenko’s plan worked, with a few hiccups here and there. He outmaneuvered his fellow pilots, evaded the Japanese air defences, avoided crashing into the 727, and managed not to destroy his precious MiG during landing. Mission Accomplished.

The aftermath

The Soviet government created a fictitious story, saying Belenko got lost and had to land in Japan. There, the Japanese officials drugged the pilot and kept him incarcerated.

The Soviets demanded the return of the jet fighter and the rebel pilot immediately. The Japanese government wanted to comply, avoiding unnecessary attrition with such dangerous neighbours. Still, the Americans pressured them to keep both for the time being, and the request was ignored.

The Japanese government was afraid the Soviets would forcefully attempt to retrieve the MiG. In the days following the landing, 200 troops were deployed to guard the airport. Tanks and anti-aircraft artillery were placed around the perimeter, and the maritime defences were also strengthened.

The Americans were allowed to inspect the jet at the airport, and on September 25, it was partially dismantled, loaded into a USAF C5 Galaxy cargo plane, and brought to Hyakuri Air Base, north of Tokyo. A banner on the plane read: “Goodbye people of Hakodate, sorry for the trouble.”

After a thorough inspection, the Americans realized the Foxbat was “too much barking for too little biting.” It was fast but fuel-guzzling, and the engines were prone to overheating. Its radar was powerful, Belenko said it could kill rabbits in the fields if turned on during taxing, but it was outdated.

Due to a lack of funds and expertise, the Soviets didn’t utilize advanced materials like carbon fiber or titanium, and the plane was primarily constructed from steel, resulting in excessive weight and poor maneuverability.

Belenko’s Foxbat was eventually packed into 40 boxes, and on November 15, it was shipped to the Soviet Union. The Soviets complained that around 20 pieces were missing.

After the incident, the relationship between Japan and the Soviet Union went sour. The Soviets sent a $10 million bill for the missing/damaged parts, and Japan charged the Soviets $40,000 for the damage to Hakodate Airport and shipping costs. Neither bill was ever paid.

Lieutenant Belenko was sent to prison for breaking into the Japanese airspace, but his request for asylum in the USA was granted by President Gerald Ford. Later on, President Jimmy Carter signed his American citizenship.

Viktor Belenko moved to the US, was debriefed extensively by the CIA and US military, learned English, and gradually adapted to life in the US. For a while, he was afraid that the KGB would send agents to kill him. For a few years, he kept himself quiet, living under the radar. The story of his life in the Soviet Union, his defection, and his early time in the US was written by John Barron in the book MiG Pilot: The Final Escape of Lieutenant Belenko, published in 1980. Belenko later became a consultant to the US military and aerospace industry, a public speaker, and a businessman. He also married an American woman and had two children.

All the data collected by the American military, including the MiG-25 pilot’s manual that Belenko brought with him, helped the development of the McDonnell Douglas F-15, which became the best fighter interceptor of the Cold War. (Pictured above).

The MiG-25 had a short career. The Soviets retired the plane in 1984. It still holds the absolute world record for altitude achieved by a production jet aircraft. In 1977, a MiG-25 reached an altitude of 37,650 meters (123,523 feet).

A Soviet committee later visited Chuguyevka Air Base and was shocked by what they found there. They immediately decided to improve conditions and built a five-story government building, a school, a kindergarten, and other facilities. Treatment of pilots in the Russian Far East region improved significantly. Were the commies concerned with the well-being of their personnel or just afraid that Belenko’s daring escape could inspire other pilots? Perhaps both, who knows?

The luckiest man alive.

Part of the info I wrote here came from a write-up by the investigative journalist Susan Katz Keating, published on the Soldier of Fortune website. There, she describes an encounter with Belenko at the Reno Air Races. Here is how she finished the article:

– That day when Belenko and I met at the Reno Air Races, he was jovial, happy, and full of jokes. I asked him if he was glad he defected.

“Of course!” he grinned. “I have a good life here in our country, the United States of America.”

We sat watching the race planes whiz through the sky. The pilots pulled tight corners, rounding far pylons as they flew the course, battling to outrun one another. Even from the ground, it was thrilling.

I asked Belenko if he planned to do any gambling while he was in Reno.

“I should,” he laughed. He waved at the lead plane, urging him onward. “I am the luckiest man alive!” –

Viktor Belenko quietly passed away on September 24, 2023, following a brief illness. His sons Tom and Paul were at his side.

Captivating stories! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Nancy. I am happy you have enjoyed.

LikeLiked by 1 person