When the Brazilian president, Getulio Vargas, and Theodore Roosevelt reached an agreement on our cooperation in the war effort, the idea was not only to send army troops to Italy but also to deploy our navy and Air Force.

The Lend and Lease Act. allowed the young Brazilian Air Force to replace its obsolete equipment with top-notch American aircraft. These are some of the machines we received:

For advanced training and ground support duties, the North American Texan T6.

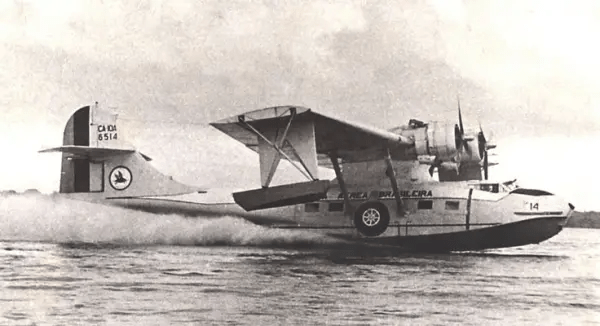

For coastal patrol and anti-submarine activities: the Consolidated PBY Catalina.

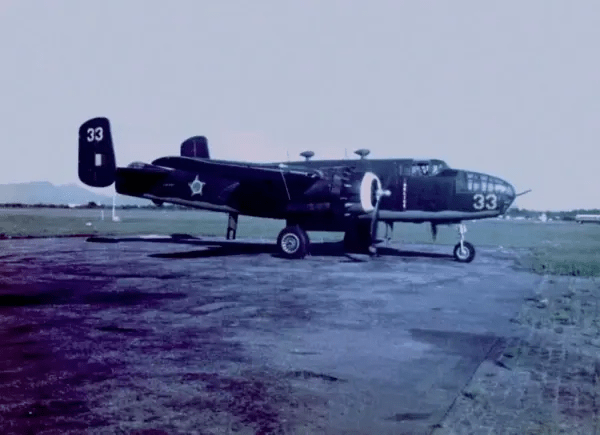

As a medium bomber: the North American B25 Mitchell.

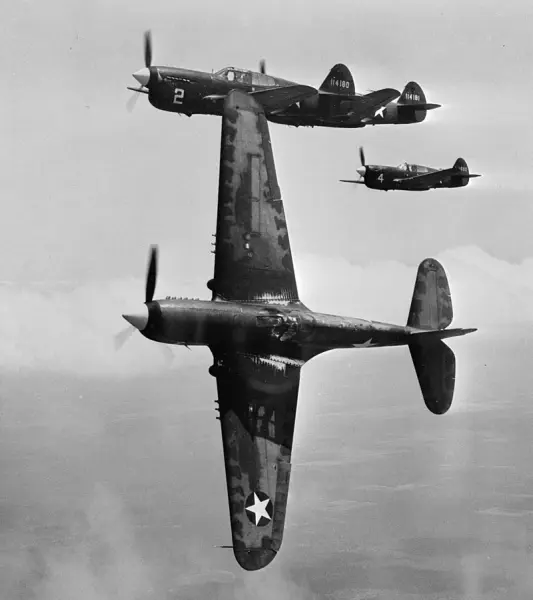

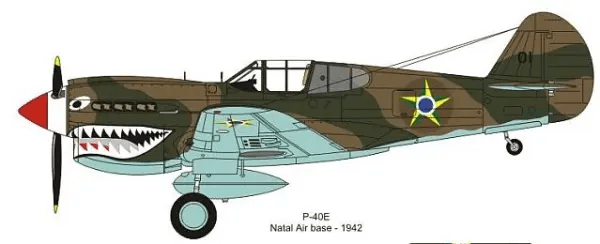

The Curtiss P-40 became our main interceptor.

And the versatile fighter/bomber Republic P-47 Thunderbolt.

Flying Fast.

In January 1944, 43 Brazilian pilots (all volunteers) from the 1st Fighter Squadron were sent to the USAF base at Aguadulce, Panama, to learn how to fly the P-40 Warhawk. For most of them, that would be the first contact with a high-performance fighter.

According to the instructors, the Brazilian pilots progressed quickly and soon they were comfortably flying as an independent unit, even performing patrol and defense mission around the Panama Canal.

With its “shark” nose art, the Warhawk is, perhaps, the most recognizable WWII fighter. The airplane became the backbone of the Brazilian Air Force fighter squadrons, but it was not the machine chosen to fight in Italy.

During the war, our Warhawks were kept in Brazil to protect the homeland.

The P-40 had a long career in the Brazilian Air Force. Even after the arrival of jet fighters in the early 1950s, FAB kept the P-40 operational as a trainer at many military aviation schools until 1958.

The Final Training.

After 160 flight hours in the P-40, in June 1944, the pilots and the ground crew were sent to Suffolk Air Base on Long Island, NY, to start the training in the P-47 Thunderbolt.

At this stage, the Brazilians were comfortably flying as a tactical unit, and they didn’t take long to get used to the new fighter’s qualities.

The Jug

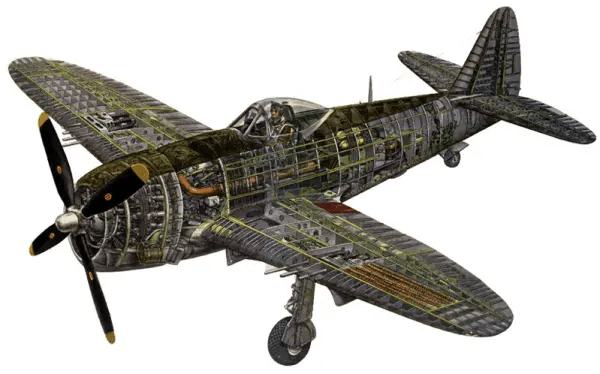

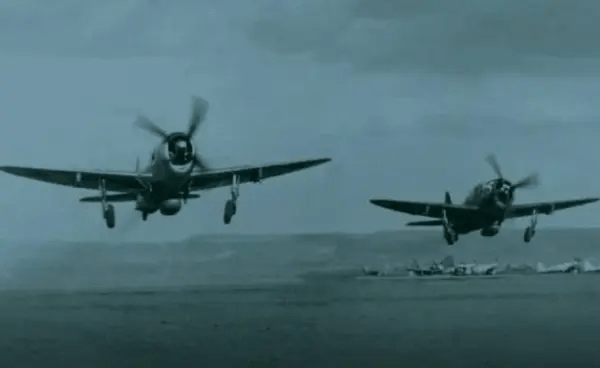

The first prototype of the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt flew on May 6, 1941, and it was a mix of revolutionary and conservative projects.

The Thunderbolt was big but maneuverable, built like a tank yet fast. It was a multi-role warplane capable of performing tasks such as interception, escort, ground support, light bombing, and reconnaissance.

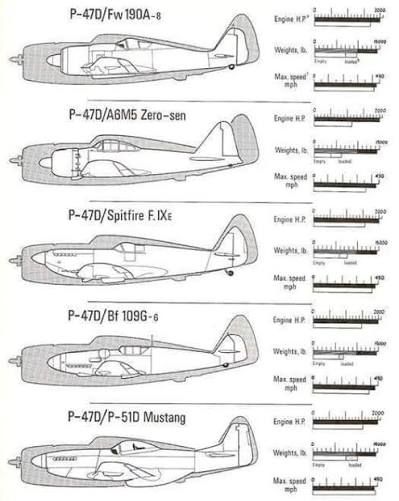

And how big was it? It was three feet wider than the P-51 and four feet longer. And at more than 10,000 pounds empty, it was about 50 percent heavier than the Mustang and nearly twice the weight of the Spitfire.

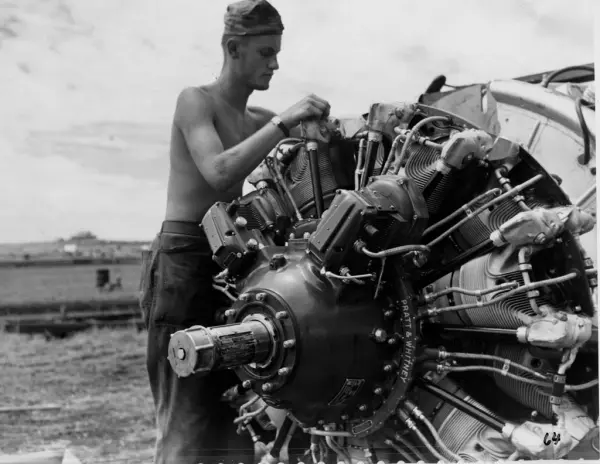

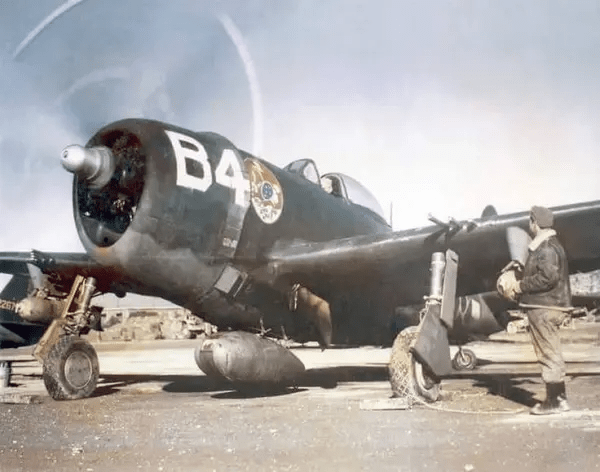

The P-47 is not a pretty airplane to look at; it doesn’t have the beautiful, aerodynamic lines of its brothers-in-arms, the Mustang and Spitfire. Pilots and ground crew nicknamed it “The Jug.” It was designed around the “hot rod” aircraft engine of the time, the Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp.

It is an 18-cylinder, air-cooled, radial engine with 2800 CID (around 46 liters). On the latest turbo/supercharged versions, it could deliver over 2500 hp, and in “emergency mode” with water/alcohol injection, it could reach 2800 hp. Enough power to keep the Thunderbolt head-to-head in the top speed with the Mustang at 440 miles per hour

The Double Wasp could also be found in other top performance fighters like the Hellcat and Corsair.

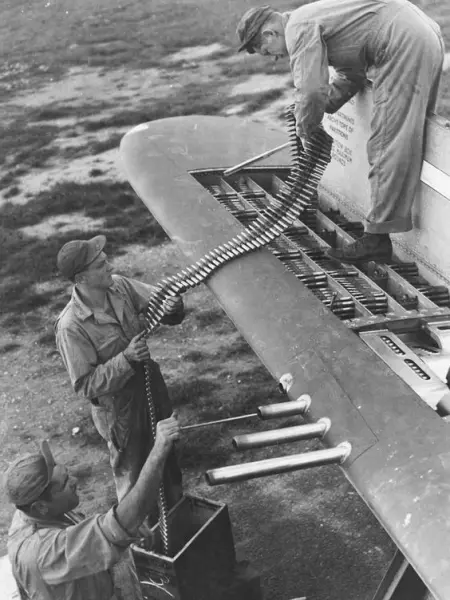

The Thunderbolt firepower was superb as well. Equipped with eight 0.50 cal Browning machine guns and room for nothing less than 3400 rounds (the Mustang could pack only 1800 bullets). It was enough for a full 30-second blast. As a Brazilian pilot once said: “If you had enough bullets in your pocket, you could cut a German train car in half”.

Between 1941 and 1945, a little over 15,600 P-47s were built. Just like the P-40, the Thunderbolt was employed in every theatre of the war and exported to most Allied countries.

Into enemy skies

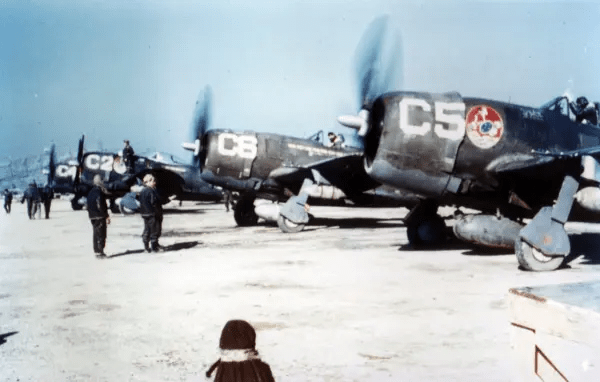

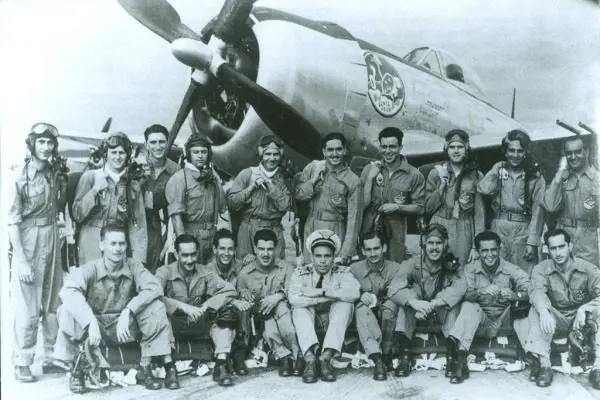

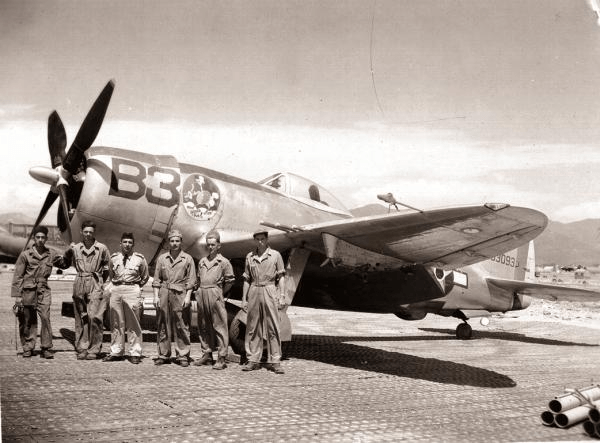

The 1st Fighter Squadron (1º GAvCA in the Brazilian Air Force code) arrived in Italy on October 6, 1944. The pilots were divided into 4 squadrons:

- Red Squad (letter “A”)

- Yellow Squad (letter “B”)

- Blue Squad (letter “C”)

- Green Squad (letter “D”)

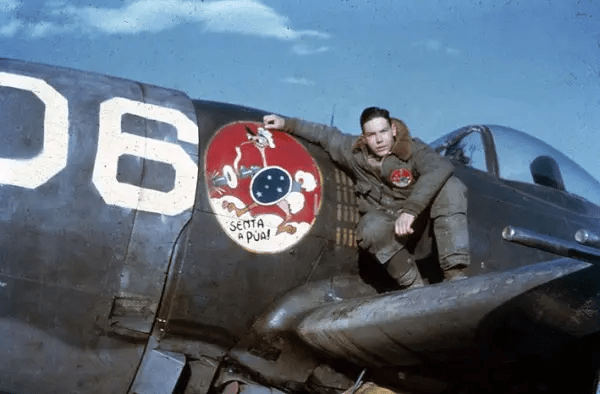

The Squadrons were equipped with the P-47 Thunderbolts from the local USAAF warehouse. The fighters received the FAB’s green-and-yellow star and identification codes.

Soon, Brazilian pilots were routinely flying combat missions. It was now time to apply everything they had learned in training to support the powerful Allied force that would soon defeat the German war machine.

Their baptism of fire happened on November 11, 1945, when the 1º GAvCA attacked some German deposits. At this point, they were still based in Tarquinia. After a couple of months, they were officially transferred to the 350th Fighter Group, based in Pisa, until the end of operations on July 1, 1945.

Pisa is a city in Italy’s Tuscany region best known for its iconic Leaning Tower. To give an idea of how close they were to Germany, Pisa is 311 miles from Munich.

Senta a Púa!

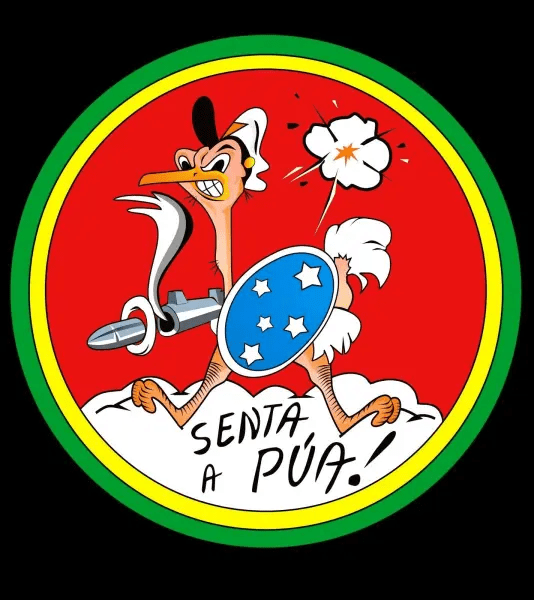

Since their training days in Aquadulce, the Brazilian 1st Fighter Squadron has had a battle cry: ” Senta a Púa“. It is not easy to translate into English; it is something like an imperative voice saying: “Hit with a bat or spear”. But it was only after a few weeks in Italy that they decided to create the symbol.

The drawing is full of meanings: behind the bird there is flak exploding; the red background is the skies stained with the blood of those who died in combat; the shield represents the Thunderbolt’s armor; the stars on the shield are the “Southern Cross”, one of the Brazilian national symbols; and the bird shooting a gun represents their very mission.

But the question is: Why did those crazy guys choose an ostrich? A damn bird that just can’t fly? The answer is, again, tied to our good sense of humor.

For most of our crew, one of the biggest challenges of the war was eating the dreadful American canned food. They used to say to each other, “To survive the German flak, you need skills and a lot of luck, but to survive the canned food, you need an ostrich’s stomach.” So, they considered themselves a bunch of fighting ostriches.

Ground Attaks

The best role for the massive Thunderbolt was ground attack; fully loaded, it could carry 3,000 pounds of bombs and rockets, almost half of the B-17 Flying Fortress’s payload.

Since its performance in dogfights was less than ideal, the P-47 pilots had different tactics to engage enemy fighters, as Brigadier Nero Moura recollects: “During our training, the Americans made very clear our mission was ground attack, but that didn’t mean we were forbidden to shoot at enemy planes.”

Our instructors repeated the Thunderbolt golden rules for dog fights a thousand times: Fly high, dive fast, hit hard. If you got the bastard, great; if you didn’t, keep moving. You will get him next time.”

Built like a tank

Among all the qualities that made the Thunderbolt a superb machine, perhaps the one most pilots keep in a special place in their memories is the plane’s amazing capacity to take punishment and still bring its pilot home.

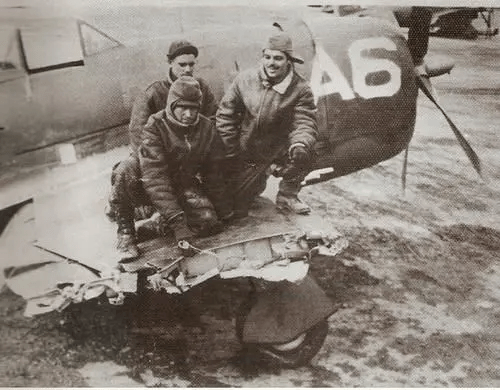

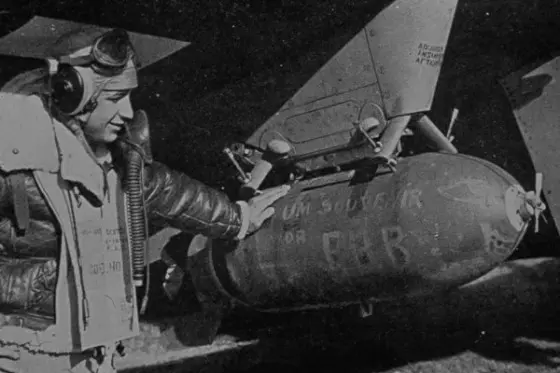

The picture above was taken on Jan 27, 1945. It shows the damage on the P-47 flow by Lt. Raymundo Costa Canário (canário means “canary”). What tore off a 4-foot-long piece of the wing wasn’t a well-aimed German flak. It was something much more embarrassing to the pilot.

That day, Lt. Canário was flying a low-level ground-attack mission, and thanks to his inexperience, the 20-year-old aviator crashed his plane into a massive factory chimney. Even with a big chunk of the right wing gone, he was able to keep his Thunderbolt flying all the way back to base. During the trip, he was escorted by his squadron leader, Cap. Dorneles.

They took a longer route home, flying over the ocean to avoid German anti-aircraft batteries.

To make things worse, at some point, they were mistaken for enemy airplanes and attacked by a pair of patrolling Spitfires. Thank God the Brits soon realized their mistake and quickly left the scene.

They both landed safely, astonishing everyone at the base. This further proves Thunderbolt’s incredible reliability.

Canário’s P-47 was destined for the scrapyard, but the Lieutenant wasn’t ready to part ways with his beloved machine. He insisted it could be repaired, and together, they flew 50 more missions until the end of the war.

The FAB’s Finest Hour.

The FAB had a short participation in the war but was a very intense one.

They faced many obstacles, just like any other allied soldier, a fierce enemy, a harsh winter, and homesickness. But perhaps one of the most cruel of them was our very own government.

Everyone knew that our president didn’t want to fight in this war, and our soldiers suffered because of his reluctance.

Getulio Vargas never allowed FAB to send enough replacements to cover the pilots lost in combat.

The result was that after only 6 months, the First Group was reduced to only 22 pilots. Too few to keep them flying as a group.

The next step would be dismantling the unit and dispatching the remaining pilots to other groups throughout Europe as replacements.

But the guys refused to break apart. They were born as a group and should die as one.

The commander of the 350th was straightforward: “If you guys want to keep the First Group alive, it means one thing: each one of you will have to fly your own mission and the mission of that guy who never came as well”.

From that point to the end of the war, Brazilian pilots often flew 2 missions a day, and during the final Allied push, they even flew 3 daily missions.

During its short contribution in WW II, the First Fighter Group flew a total of 445 bombing missions.

From the original 43 pilots who arrived in Italy, 9 were shot down and died, 5 were made POW, 3 bailed out over enemy territory and were rescued by Italian families and 15 were sent home because of medical issues.

April 22 is the most crucial day in the history of the “Força Aérea Brasileira”. On this day in 1945, FAB set its own record when the 23 pilots of the First Fighter Group flew 44 bombing missions in 24 hours over the Nazi-occupied territories in Italy.

Back home, FAB officially announced that April 22 would be a day to honor those who fought and died in the skies of Europe during WWII, as well as future fighter pilots. It is called “The National Hunter Pilot Day” because in Portuguese, they are not fighters. They are hunters.

In 1986, Colonel Ariel Nielsen, former Commander of the 350th Fighter Group, pledged on behalf of the Brazilians that the American government would award them the “Presidential Unit Citation.”

FAB became the third foreign Air Force to receive the honor.

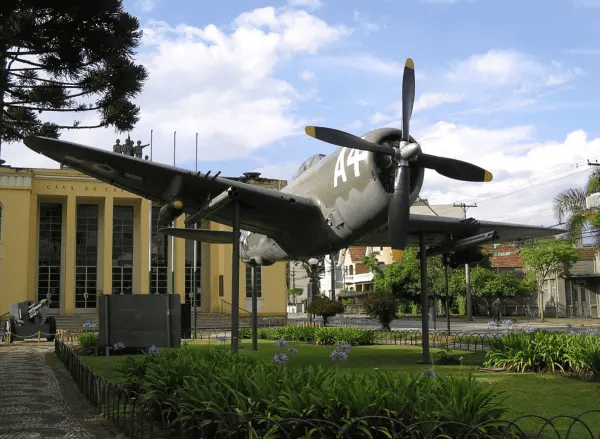

A monument dedicated to freedom

In my hometown, Curitiba, there is a fascinating museum that honors Brazilian soldiers, airmen, and sailors who fought in WWII. In front of the building, there are some static pieces on display: a captured German cannon, a torpedo, a light tank, and a P-47 Thunderbolt.

Since I was old enough to understand what an airplane was, I would bother my father to take me there to see “the airplane”. For a 5-year-old kid, that Thunderbolt wasn’t big… it was gigantic.

Many years later, when the teachers and the books taught me about the war and the reasons we fought, that plane became even bigger. It certainly inspired me to join the FAB in 1988.

The Thunderbolt will fly again.

The FAB Museum in Rio de Janeiro has been working hard to put together a P-47 to become the only fly-worthy unit in the country.

The main source for parts is the Thunderbolts on static display across the country.

The one in Curitiba proudly gave its brake system.

It’s fascinating to learn about the Brazilian pilots and the aircraft they skillfully flew during WWII. They were so courageous! The P-47 Thunderbolt-totally awesome!. 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks, Nancy. I am happy you enjoyed the article. Our participation in WWII still is a bit obscure, not a lot of people know about it. Thanks to the internet, now it is easier to share their experiences.

LikeLiked by 1 person