The year was 1961, Elvis Presley, still enjoying his status as “The King of Rock’n Roll”, had just released the song Little Sister. In the same year, Jaguar launched the legendary E-type, celebrated ever since as one of the world’s most beautiful cars. Also in 1961, people around the world were thrilled watching Gregory Peck and David Niven explode the heck out of a secret nazi base in the movie “The Guns of Navarone” (picture below).

In other words, people were trying to live their lives as best as they could, but the peace that we were expecting after WWII never came. The free world, led by the United States, was gearing up for an inevitable confrontation against the Soviet Union, in a war that would most likely wipe out civilization from the face of the earth.

The year 1961 was, in many aspects, the peak of the so-called Cold War. In April, the CIA organized the disastrous invasion of Cuba, at the Bay of Pigs. In August, the Soviets began the construction of the Berlin wall. The recently elected American President John F. Kennedy, suggests the population should start building backyard shelters in case of a nuclear war.

The western nations had grossly overestimated the capabilities of the Soviet army. Based on the data available at the time, they believed the commies had millions of strong, well-trained soldiers equipped with state-of-the-art hardware, ready to invade the free Europe at a moment’s notice.

The allies were certain that they couldn’t stand a chance against the Soviets in a traditional “mano-a-mano” infantry warfare. To compensate this weakness they heavily relied on nuclear weapons.

The Americans built up a vast arsenal of nuclear artifacts hoping the perspective of seeing Moscow and other major Soviet cities transformed into a huge parking lot would stop the enemy from having some bullying ideas. Obviously, the Russians did the same.

The preferred methods of delivering those nuclear bombs were ballistic missiles, (usually hidden underground), submarines, and jet bombers. Both sides spent ridiculous amounts of money building formidable machines capable of annihilating whole cities with the push of a button.

The paranoia of nuclear armageddon became part of our everyday lives, not only when kids came home talking about the nuclear strike drills they have at school, but sometimes, in a much deeper and dangerous way.

During those crazy years when the mighty American war machine was extremely busy getting ready for total war, it wasn’t unusual for the military to make some mistakes or to get involved in accidents that inevitably would put civilian lives in danger. Among all those near-catastrophic events, there is a particularly shocking one.

Right at the beginning of the infamous year of 1961, the US Air Force accidentally dropped two Mark 39 hydrogen bombs over Goldsboro, North Carolina, on January 23. Miraculously those artifacts didn’t detonate and thousands of lives were spared that day. To understand the details that lead to this accident, we need to learn about a specific nuclear attack strategy of the US Air Force.

Operation Chrome Dome.

Now, that more than half a century has passed, we all know that neither the Soviets nor the Americans had the intention to start a nuclear war, but back then both sides lived in absolute fear of it. The name of the game was never to be the first one to push the button but in case of being attacked, the retaliation time was crucial.

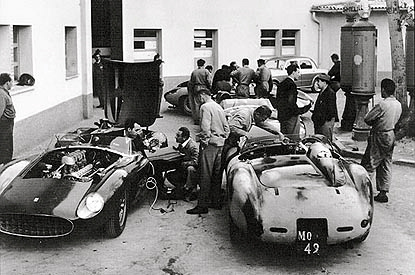

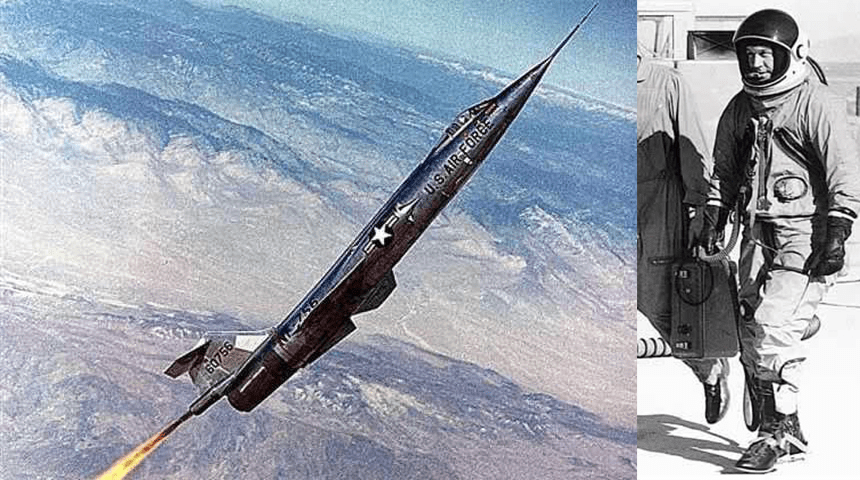

In the early 1960s, USAF General Thomas A. Power, came up with an interesting idea: in order to reduce the reaction time to a minimum, the Air Force would keep B-52 Stratofortress bombers, armed with thermonuclear weapons, flying continuously 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The airplanes would take turns flying a loop path starting from their air base all the way to Alaska, pretty close to the border with Russia, and back to the base.

The map above shows the route operated by the 49th Bombardment Wing, based on the Shepherd Air Force base, in Texas. Other wings conducted similar missions with different names like Head Start, Hard Head, Round Robin, and Operation Giant Lance.

Even the B-52s of the Strategic Air Command, in Europe, took part in this continuous airborne alert. Their mission was to attack the Soviet Union through the eastern border.

The Goldsboro crash.

On the 23 of January 1961, a B-52 took off from Seymore Johnson Air Force Base, in Goldsboro, North Carolina, for another “rapid first-strike” mission. Major Walter Scott Tulloch was the bomber commander and his plane was hauling two Mark 39 nuclear bombs. Each artifact was classified as “4 megatons”, in other words, the equivalent power of 4,000 tons of regular TNT, or 250 times more powerful than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima.

Around midnight Major Tulloch flew his B-52 to a rendezvous with a tanker, to perform aerial refueling. The extra fuel was necessary to finish the flight.

It seemed to be another uneventful mission but things started to go sour when the crew of the tanker plane sent a message to the commander telling him that his bomber was leaking fuel from the right wing tank. The refueling procedure was aborted.

Tulloch immediately alerted the ground control about the problem and he was instructed to fly a holding pattern over the Atlantic ocean, close to the coast, until most of the fuel was consumed, making it safe for landing.

However, when the B-52 reached its assigned position, the pilot reported that the leak had worsened and that 37,000 pounds (17 tons) of fuel had been lost in three minutes. The aircraft was immediately directed to return and land at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base

At this point, the disaster started to unfold. The unbalanced condition created by the disproportionate fuel load made the bomber increasingly difficult to maneuver. As the B-52 descended through 10,000 feet (3,000 m) on its approach to the airfield, the pilots were no longer able to keep it in control. The right wing broke off and the massive bomber started to spin violently, falling off the sky like a hammer. Major Tulloch ordered the crew to abandon the ship, which they did at 9,000 feet (2,700 m). Five men landed safely after ejecting or bailing out through a hatch. One did not survive his parachute landing, and two failed to leave the aircraft in time.

As the B-52 was disintegrating on its way to the ground, at 2000 ft (610 meters), the two thermonuclear bombs separated from the airplane.

The first bomb followed all the standard procedures as if it was released during a real combat mission. Three of the four arming mechanisms were activated after the separation causing it to execute several of the steps needed to arm itself, such as charging the firing capacitors and deploying a 100-foot-diameter (30 m) parachute. The recovering crew found it dangling from a tree, just a few feet from the ground. (picture above).

The aircraft wreckage covered a 2 square mile (5.2 km2) area of tobacco and cotton farmland, located at Faro, about 12 miles north of Goldsboro. The parachute of the second bomb failed to deploy and it plunged into a muddy field at 700 km/h. The Air Force personnel had to dig a 6-meter-deep pit to rescue pieces of the bomb.

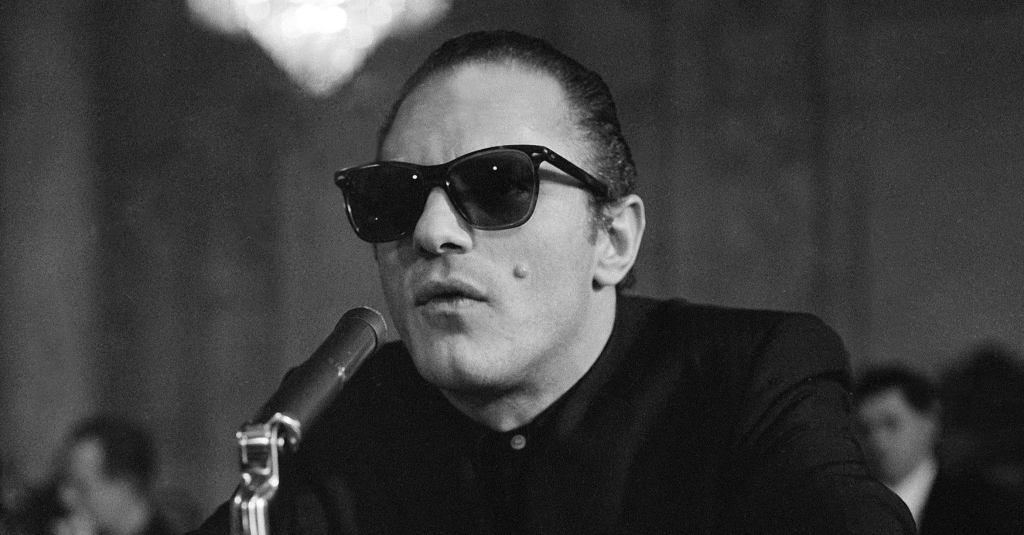

Lt. Jack ReVelle, the explosive ordnance disposal officer responsible for disarming and securing the bombs from the crash site, has a chilling memory from the moment the arm switch of the second bomb was found:

Until my death, I will never forget hearing my sergeant say, “Lieutenant, we found the arm/safe switch.” And I said, “Great.” He said, “Not great. It’s on arm.”

The excavation of the second bomb was eventually abandoned as a result of uncontrollable ground-water flooding. Most of the thermonuclear stage was never found but the “pit”, or core, containing uranium and plutonium, which is needed to trigger a nuclear explosion was removed. The US Army purchased a 400-foot (120 m) diameter circular easement over the buried component, to prevent any future use of the land.

The Verdict.

In 1969, Parker F. Jones, the supervisor of nuclear safety at Sandia National Laboratories, wrote a rather colorful report called: “Goldsboro Revisited” or “How I learned to Mistrust the H-Bomb“, in a clear quotation from the 1964 movie “Dr. Strange love”.

In this report, (picture above) Jones said that “one simple, dynamo-technology, low voltage switch stood between the United States and a major catastrophe”, and concluded that “the MK 39 Mod 2 bomb did not possess adequate safety for the airborne alert role in the B-52”, and that it “seems credible” that a short circuit in the arm line during a mid-air breakup of the aircraft “could” have resulted in a nuclear explosion”.

If you got this far in this article, you must be wondering (just like I am), – “Nuclear bombs don’t arm themselves, right?!” Especially if we are talking about 1960s technology. At some point, a human being must have pulled some sort of switch into an “armed” position… Right?! – Well, internet sources are pretty vague about it but other sources confirm that the decision to arm the “doomsday payload” inside a B-52 comes to the airplane commander (after receiving a Presidential order, obviously) and he must do it manually.

Well, a human being must initiate the sequence all right, not exactly moving a switch, but removing a series of “safety pins” located on the bomb itself. Believe it or not, those pins on the first bomb were not pulled by hand, but instead, they slid off thanks to the incredible centrifugal force the aircraft experienced during its spinning journey toward the ground. Thankfully, the centrifugal force wasn’t strong enough to pull the very last safety switch on the bomb, and that blessed “low-voltage” device saved the lives of thousands of American citizens.

It is a bit more complicated to understand why the second bomb didn’t explode. Here is the most reasonable explanation: when it got detached from the aircraft, all the safety pins and arms were locked in the safe position, which prevented the parachute to deploy. When the bomb smashed against the muddy terrain, the violence of the impact must have caused the safety switch to move into the arm position. The impact also broke the bomb in half, making it unable to detonate. Ufff!!!!

Final thoughts

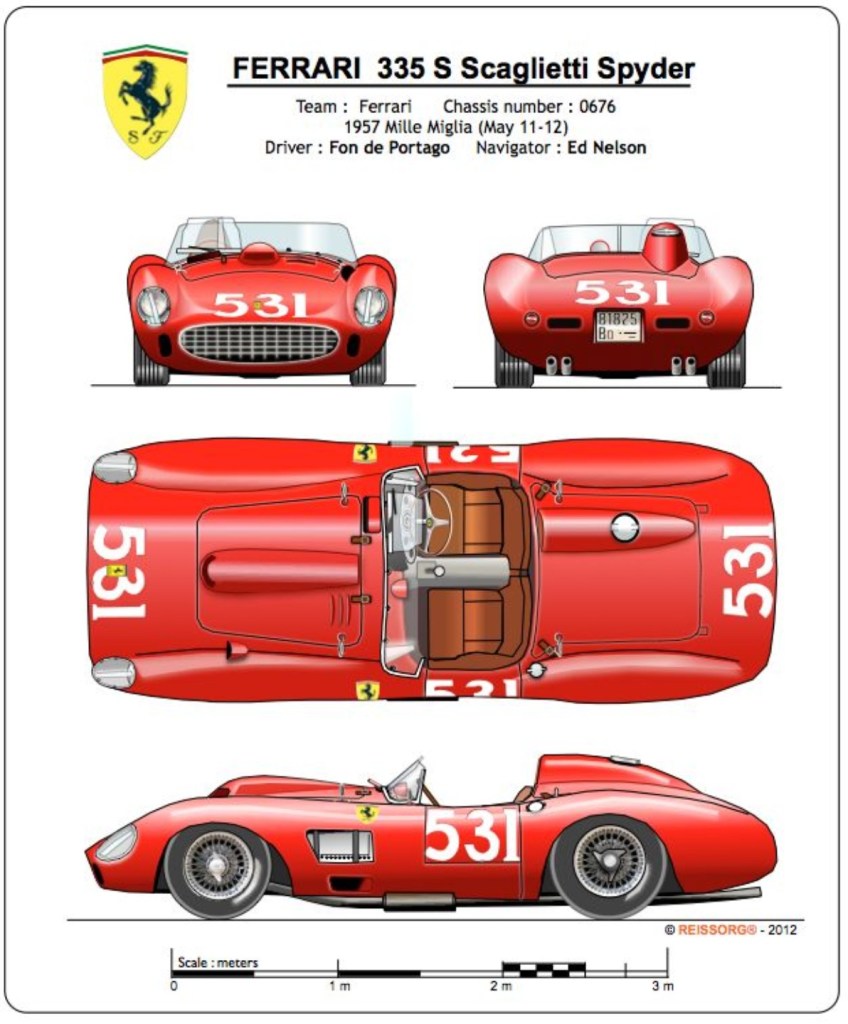

The Mark 39 was considered a “light thermonuclear weapon” It weighed 6,500–6,750 pounds (2,950–3,060 kilograms), and was about 11 feet, 8 inches long (3.556 meters) with a diameter of 2 feet, 11 inches (88.9 centimeters).

With a destructive capacity of 4 megatons, each of the Goldsboro bombs could have ignited a fireball capable to incinerate everything in a radius of 1.05 miles from ground zero, a lethal radiation zone (500 rems of radiation in an instant, when no more than 100 rems over an entire year is considered safe) extending 1.84 square miles, a pressure wave of 20 pounds per square inch that would demolish concrete buildings at a distance of 2.78 miles, a 5 PSI pressure that would collapse most ordinary buildings 6.86 miles from the blast zone, and thermal radiation hot enough to start fires and cause third-degree burns 15.2 miles from the blast site. The radiation plume would stream past Delaware almost to southern New Jersey. The death toll is estimated at 60,000.

Since we are entering the “what if” field, besides the horrific catastrophe of the nuclear explosion, the blast of one of those bombs could have sparkle a series of events leading to the total war with the Soviet Union. The recently sworn President, John F. Kennedy, (his inauguration happened just 3 days before) would have been rudely awakened in the middle of the night with the terrible news: “Sir, the United States is under attack”. Since communication between the Seymore Johnson Air Base and the rest of the world would be seriously impaired, thanks to the nuclear blast, there is no way for the government to know that explosion was, actually, friendly fire. Some officials would wonder, “Why the commies decided to drop a bomb on Goldsboro, North Carolina, instead of Washington DC, or New York? But I think this wouldn’t be enough to stop the President from authorizing a full-scale retaliation. And that would be the end of the world as we know it.

The Pentagon released a statement saying no American lives were in danger during or after the crash. The safety mechanism worked as designed, keeping the bomb from detonating. The fleet of B-52s received structural reinforcements and the bombs had their safety switches redesigned. The US Air Force carried on Chrome Dome and other similar operations until 1968 when the program was scrapped.

The Goldsboro crash wasn’t neither the first nor last time the American military “lost” or “mishandled” a nuclear device. They even have a name for it, “Broken Arrow”. But one thing is for sure, it was one of those occasions when we came pretty darn close to a nuclear armageddon. I don’t consider myself a religious guy but I firmly believe that a divine intervention that night prevented the beginning of WWIII.

* If you enjoyed this article, you can help this blog with as little as a Dollar. Please visit my “Buy Me a Coffee” page. Thank you so much for your support. *

https://www.buymeacoffee.com/rubenshotra